The slowest museum yet: 10 am to 6 pm, 8 hours total, the entire span of its opening that day. I skipped lunch so as not to lose a minute.

Thank god for the cell phone camera, and for the museum’s policy of allowing visitors to photograph works. I don’t believe the camera causes me to look any less closely, because I fortunately had that habit already established before the advent of digital photography gave me the ability to quickly capture everything that interested me. On the rare occasions when I have the luxury of time to go back and “process” the photos I took, like I am doing now, then the act of taking the photo becomes analogous to making a drawing or color study or written notes of the work in my sketchbook. In the case of a collection like this one, that is large, completely new to me, and located far enough away from where I live that it is unlikely I will visit again soon, the opportunity to photograph the artworks is a true godsend.

The first works you see upon entering the museum are four Rodin sculptures placed in front of a large Tintoretto canvas – these sculptures are truly the germ of the entire collection. August Thyssen (1842-1926) was a hugely successful industrialist who commissioned the sculptor Auguste Rodin in 1910 to create a series of seven marble figures to start a collection of sculptures. The outbreak of World War I interrupted this project; August died in 1926 and the set of Rodin sculptures passed to a branch of the family that had settled in Germany. Only in 1956 were these sculptures bought back by Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza and added to his collection.

Duccio di Buoninsegna

Christ and the Samaritan Woman

tempera and gold on panel, 1310-11

This panel was once part of Duccio’s Maestà in Siena – if you’ve been in that dark, hot room in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, you’ll remember all the empty spots in the framework built to contain the scenes that were part of the predella, and the back of the altarpiece. Those missing works are scattered in collections all over the world, now, including this one here in Madrid.

This painting raises so many questions for me, all about pottery. How does the Samaritan woman keep that jug on her head? Yes, she has a nice crown of cloth to cushion it, but when it’s full it must weigh a ton and hurt like hell. And how does it not roll off? And how does the water stay inside when it’s on its side like that? Does she turn it upright when it’s full? Why didn’t they make pots with concave bases, to better fit the shape of the skull? Why don’t we carry pots on our heads anymore? In my study of anatomy I learned that it is one of the most efficient and safe ways to carry great weight. How did we lose the practice? And the bucket in her left hand, is that also ceramic? For some reason I imagine it’s leather, or maybe metal. Since it has a rope, maybe she’ll use it to pull water up from the well.

Anonymous German

The Annunciation Triptych

tempera and gold on panel, 1350

These figures are so stylized, it’s hard to believe they’re not of this century. What beautiful contrapposto, and calligraphic outlines!

Anonymous German

Diptych with symbols of the Virgin and Redeeming Christ: Christ with the Cross as Redemptor Mundi (details)

panel, 1410

What delightfully odd paintings these are! Look closely at all the details – nothing makes sense at first. What are the strange floating buildings behind the Madonna, and why is one of them on stilts? Whose head is growing in that tree? Why is she surrounded by a wicker fence, or are those candles planted in the ground? Why is there a locked gate behind her? In the right-side panel, do you see that the cross has HANDS growing out of the ends of each wooden beam? I’ve never seen that before… Why is the hand at the base of the cross about to hit that skull with a hammer? A skull at the base of the cross usually refers to Adam, in whose dead mouth the seed of the tree from which the cross was later made was planted, before his corpse was buried. What’s up with that kneeling guy – that position can’t be comfortable, and why does he have a string over his eyes? Why is the flagpole so broken and crooked? What animal is on the altar, and why? In the upper right, why is Eve kneeling and offering Adam a skull, when clearly all Adam wants to do is take a nap? Is that snake eating an EYEBALL from the skull?? So many questions, I could look at this one for days, then spend even more days looking up the answers to my questions.

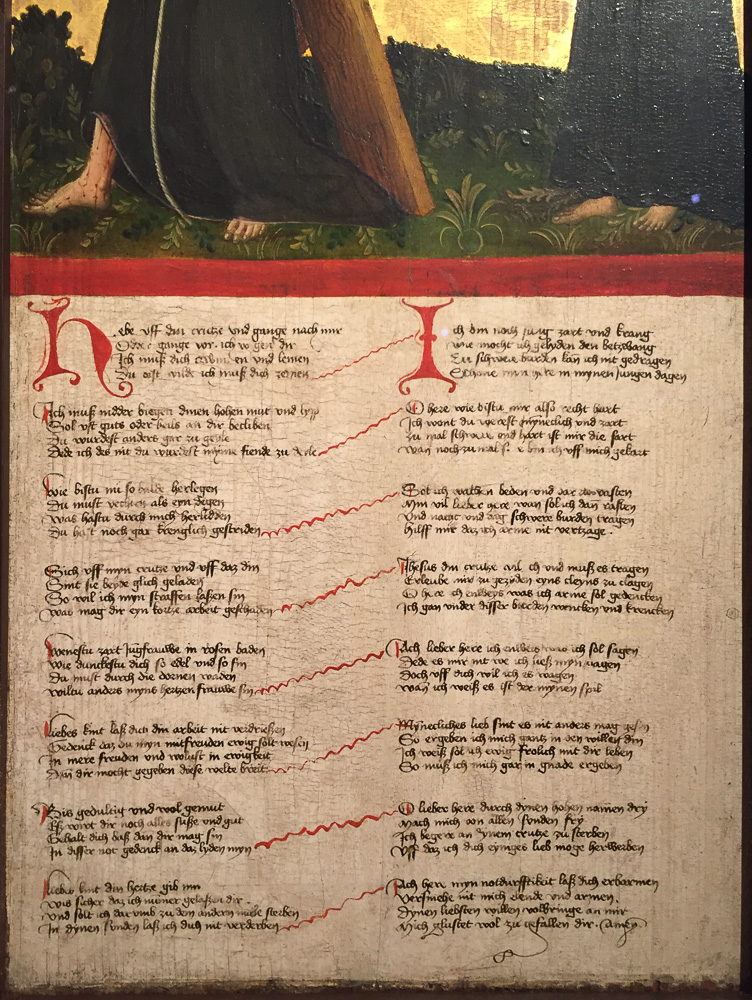

Anonymous German Artist

The Descent from the Cross (verso, detail)

oil on panel, c. 1420

This is actually the back of a painting. It has a late medieval poem (early 15th century) written out in beautiful letters, and squiggles that I think are supposed to guide you through the path of the poem, tell you the order in which it should be read. I’d like to write a letter like that one day.

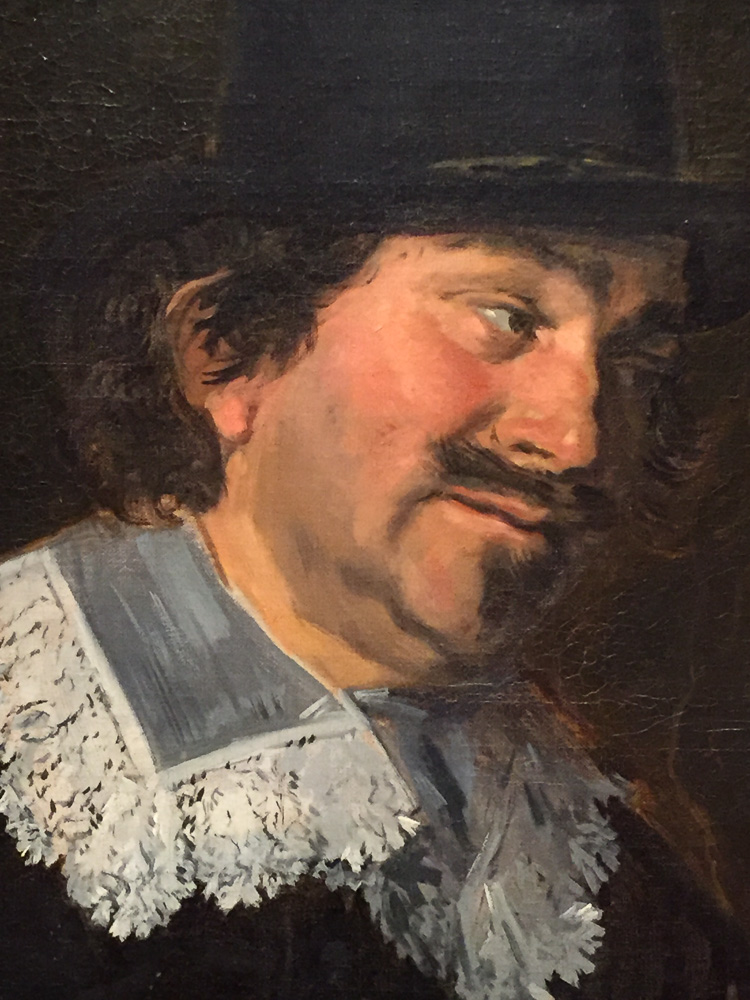

Robert Campin

Portrait of a Stout Man (Robert de Masmines?)

oil on panel, 1425

Such a beautiful, slightly worried face. This is why I’m a “realist” painter – because it’s not just about making the image look exactly like the real thing, but the philosophy of capturing life as it really is, without unrealistic idealization. Of finding the beauty in a stout man’s face.

The frame is as beautiful as the painting, which is why I included it in the photo.

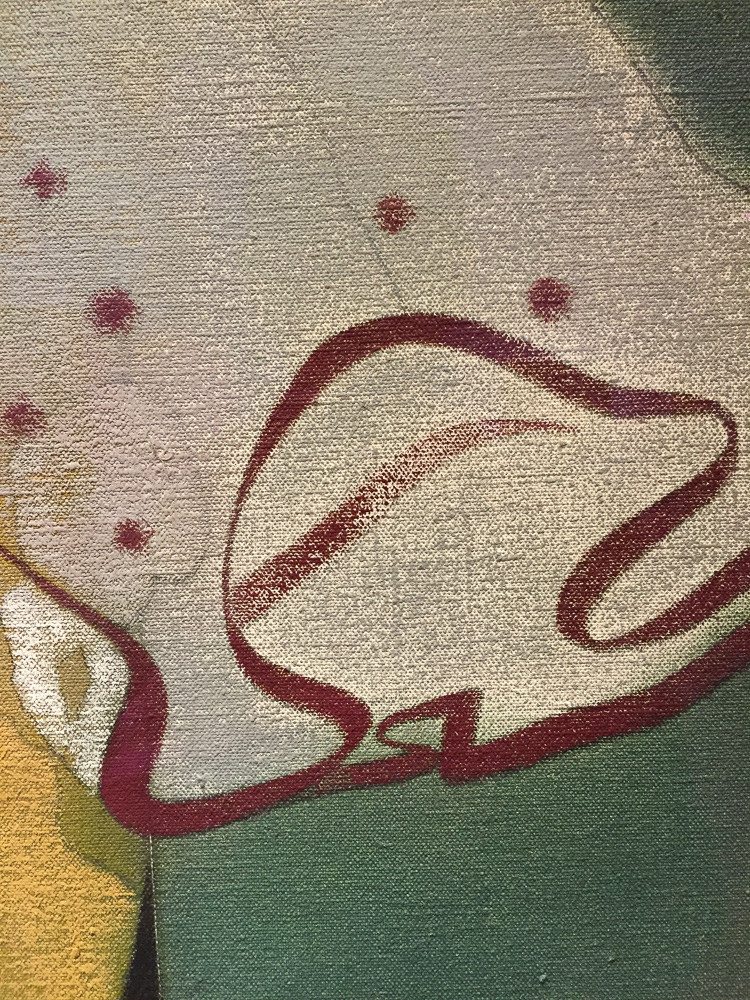

Petrus Christus

The Virgin of the Dry Tree

oil on panel, 1465

The subject of The Virgin of the Dry Tree was completely unfamiliar to me, so I had to read about it on the excellent Thyssen-Bornemisza website, which says, “It relates to the Confraternity of Our Lady of the dry Tree, to which the artist and his wife belonged….The key to the iconographic interpretation of the Virgin in this work is to be found in the Book of Ezekiel. The words ‘I the Lord […] have dried up the green tree, and have made the dry tree to flourish’ were interpreted as a clear reference to Original Sin and to Mary’s role as the New Eve. The dry tree is identified with the Tree of Knowledge, which withered following the Original Sin but which would flower again through Christ’s conception… the bent and interlaced dry branches of the tree assume the shape of a crown that clearly refers to [Christ’s] future Passion. Hanging from the branches are fifteen golden ‘As’ that symbolize the first letter of the Ave Maria or ‘Hail Mary’. The number fifteen has been related to the mysteries of the rosary, used to pray to Mary, the intercessor between man and God.”

Well, that’s all very art-historical and good… but I just like the idea of golden letters hanging from tree branches in a painting. I might steal that one day, too.

Maestro de la Vista de Santa Gúdula

Clothing the Naked (details)

oil on panel, 1470

There is a great sense of humour in this painting. This poor woman has a toddler on her head, and it’s making her cross-eyed and crazy. But look at that hand supporting her breast. It’s so graceful, and so accurately observed from life – I’ve seen nursing mothers unconsciously use exactly that configuration of the fingers. I also find it interesting that she’s using a belt around her shoulders to hold the weight of the swaddled baby.

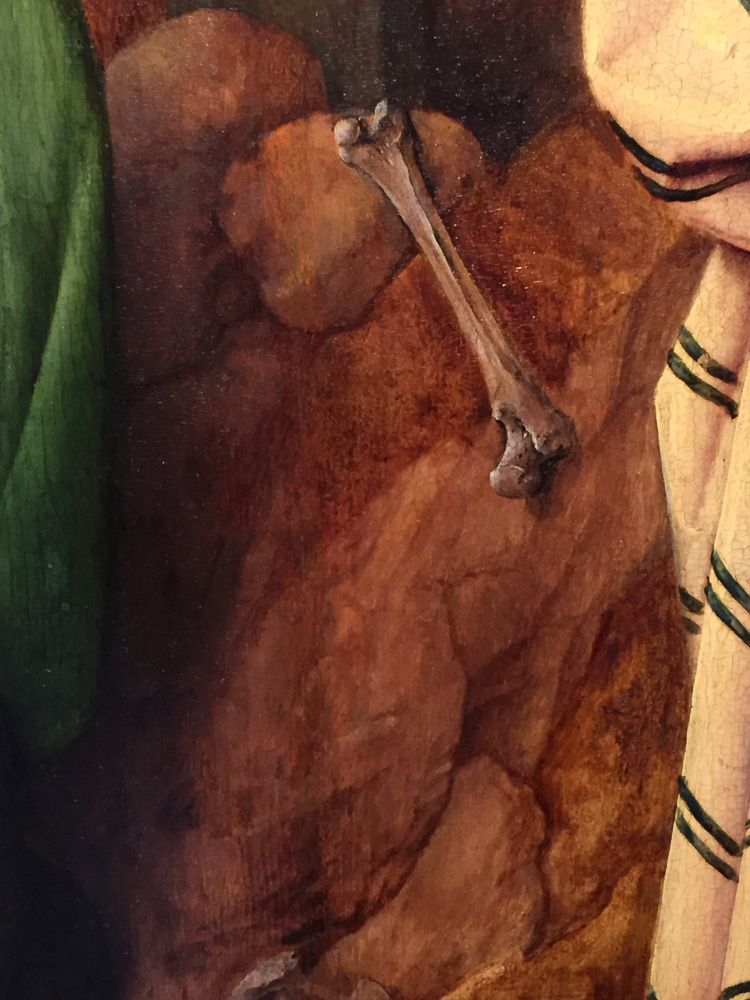

Gerard David

The Crucifixion (details)

oil on panel, 1475

Oooh, look at the indirect painting technique, the thinness of the background, the solidity of the opaque paint on that bone! Delish!

Master of the Legend of Santa Lucia

Pietà Triptych (details)

oil on panel, 1475

Realism again… in the pinkness of their eyelids that shows they have been crying, in Jesus’ dead face, so perfectly grey and slack, and in the gesture of comfort that St. John makes towards Mary. The donor-lady praying off to the side I just thought was pretty.

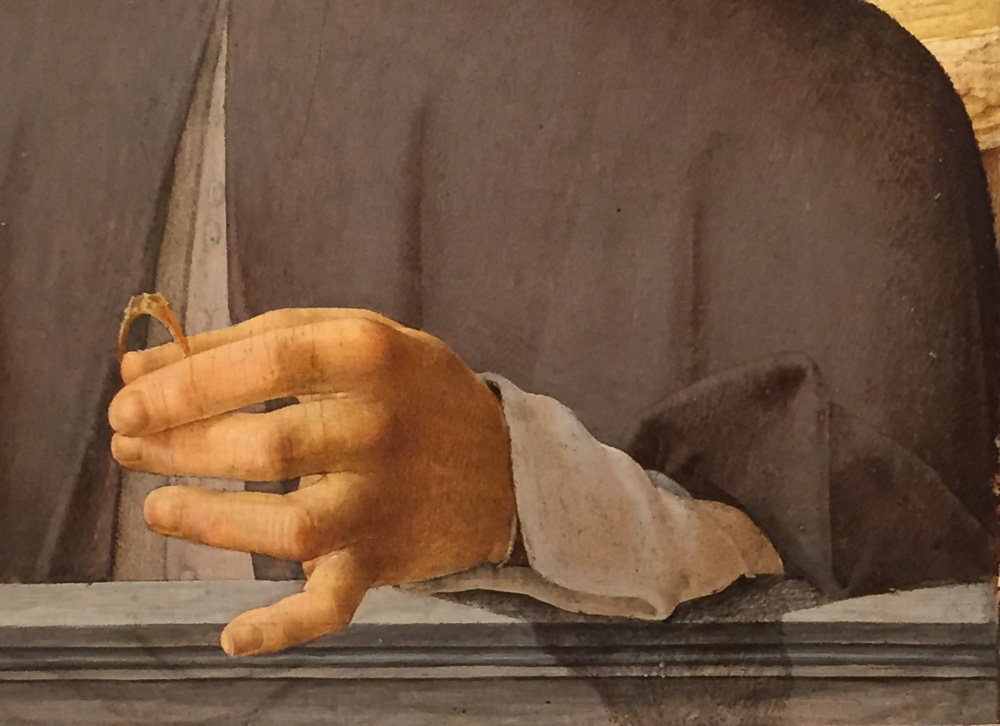

Francesco del Cossa

Portrait of a Man with a Ring (detail)

oil on panel, 1472-77

Swoon. Perfection of drawing, perfection of light.

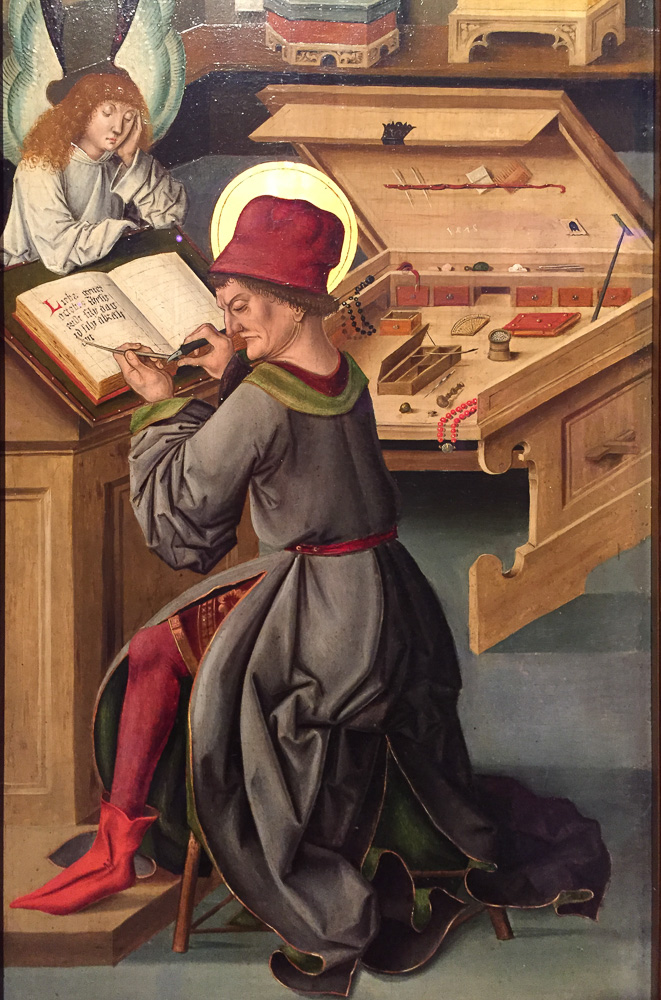

Gabriel Mälesskircher

details of:

Saint Matthew the Evangelist

Saint Mark the Evangelist

Saint Luke the Evangelist

Saint John the Evangelist

Saint Luke Painting the Virgin

all oil on panel, 1478

I love the “studios” depicted in this series of paintings by Mälesskircher – places of study, contemplation, and literary or artistic work, and all the accessories of those pursuits. I think the anachronistic “evangelist” figures may have just been an excuse for this artist to paint the books, pens, penknives, inkwells, quills, blotters, hourglasses, bottles, leather-bound books, scrolls, scissors, wax seals, folded letters, and desks with little drawers and hidden compartments that are in these scenes. I wish I had a worktable that opened up like St. Matthew’s, and an upright bookrack to hold my book open for copying.

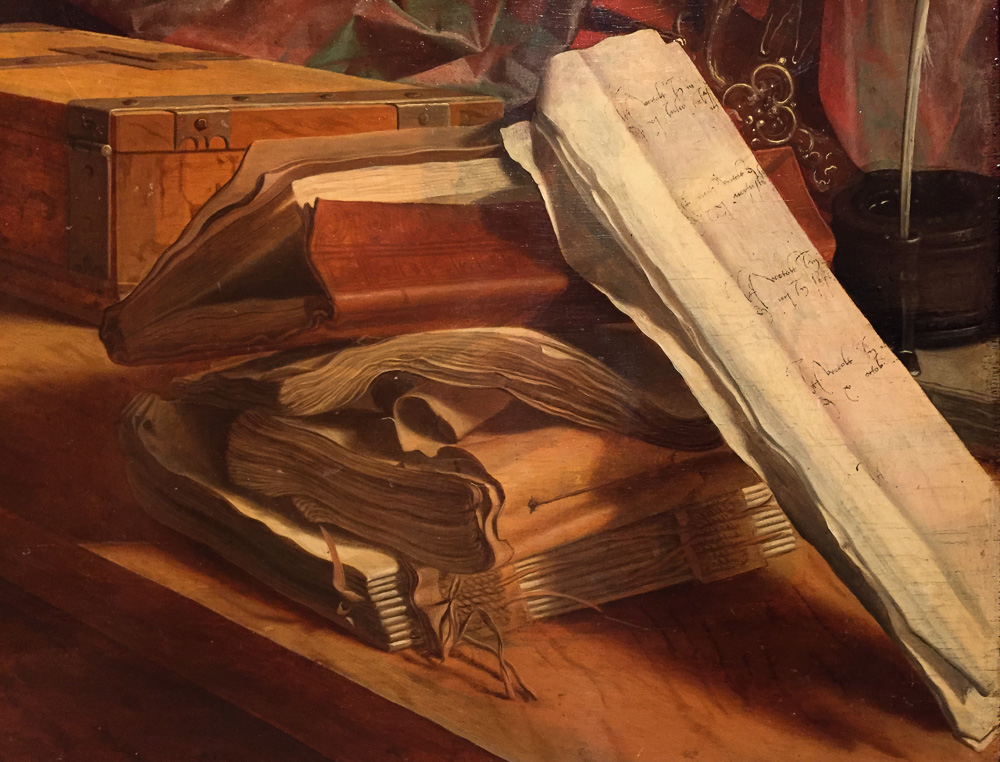

Gabriel Mälesskircher

The Martyrdom of St. Mark (detail)

oil on panel, 1478

To be working peacefully at your desk, in your studio, and then to suddenly be dragged through the streets of Alexandria by a rope about your neck, until you’re dead. One’s fate can change in the blink of an eye. This painting makes me want to get my affairs in order, and keep them there.

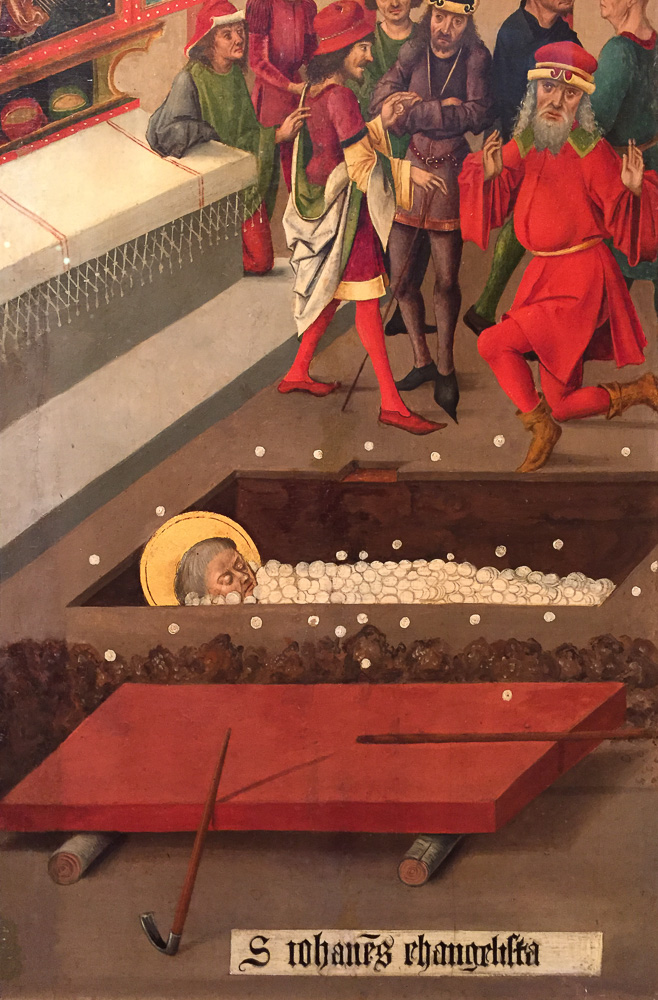

Gabriel Mälesskircher

The Miracle of the Hosts at the Tomb of St. John (detail)

oil on panel, 1478

I had to look this one up, as I had never seen anything like it before…

Mälesskircher depicted a miracle that was said to have taken place when St. John, having had his own death prophesied to him by Christ, ordered his grave to be dug near the church where he habitually preached, and then laid himself in it. The grave filled with a glowing light; after it was extinguished, John’s body was gone and instead the space was filled with a dust-like substance that believers called “manna” (but which for some reason Mälesskircher interpreted in his painting as Hosts). It was said that for approximately the next one thousand years, each year on May 8th there came forth from the grave of the holy Apostle John a fine ash-dust, which believers gathered up after an all-night vigil, and subsequently used to make medicines which could heal every sickness. The most elaborate description of the miracle dates to 1304 by Catalan Muntaner:

“On Saint Stephen’s day, every year, at the hour of Vespers, it comes out of the tomb (which is four-cornered and stands at the foot of the altar and has a beautiful marble slab on the top, full twelve palms long and five broad), and in the middle of the slab there are nine very small holes, and out of these holes, as Vespers are being sung on St. Stephen’s day, (on which day the Vespers are of St. John), manna like sand comes out of each hole and rises a full palm high from the slab, as a jet of water rises up. And this manna issues out . . . and it lasts all night and then all Saint John’s day until sunset. There is so much of this manna, by the time the sun has set and it has ceased to issue out, that, altogether, there are of it full three cuarteras of Barcelona [about 120 quarts]. And this manna is marvelously good for many things; for instance he who drinks it when he feels fever coming on will never have fever again. Also, if a lady is in travail and cannot bring forth, if she drinks it with water or with wine, she will be delivered at once. And again, if there is a storm at sea and some of the manna is thrown in the sea three times in the name of the Holy Trinity and Our Lady Saint Mary and the Blessed Saint John the Evangelist, at once the storm ceases. And again, he who suffers from gall stones, and drinks it in the said names, recovers at once. And some of this manna is given to all pilgrims who come there; but it only appears once a year.”

Hans Memling

Flowers in a Jug (verso)

oil on panel, 1485

A fine jug, a fine rug, a wonderfully atmospheric niche for them to sit in.

Juan de Flandes

Portrait of an Infanta (Catherine of Aragón?)

oil on panel, 1496

Juan de Flandes

The Lamentation Over the Dead Christ (detail)

oil on panel, 1500

Probably one of the Marys, off to the side of this crucifixion… but she’s exactly what I imagine Cinderella looks like.

Bernhard Strigel

The Annunciation to Saint Anne (detail)

oil on panel, 1505-10

Poor St. Anne. She really doesn’t want to be pregnant.

I love this one for its use of ribbons to indicate speech, and scrolls to help the story along.

Jokob and/or Hans Strüb

The Visitation (detail)

oil on panel, 1505

Mary and Elizabeth with x-ray views into their wombs. I love the crazy ways that artists find to give information and tell stories via pictures.

Giovanni Bellini

Nunc Dimittis (details)

oil on panel, 1505-1510

fabric stoffa drapery loveliness

Vittore Carpaccio

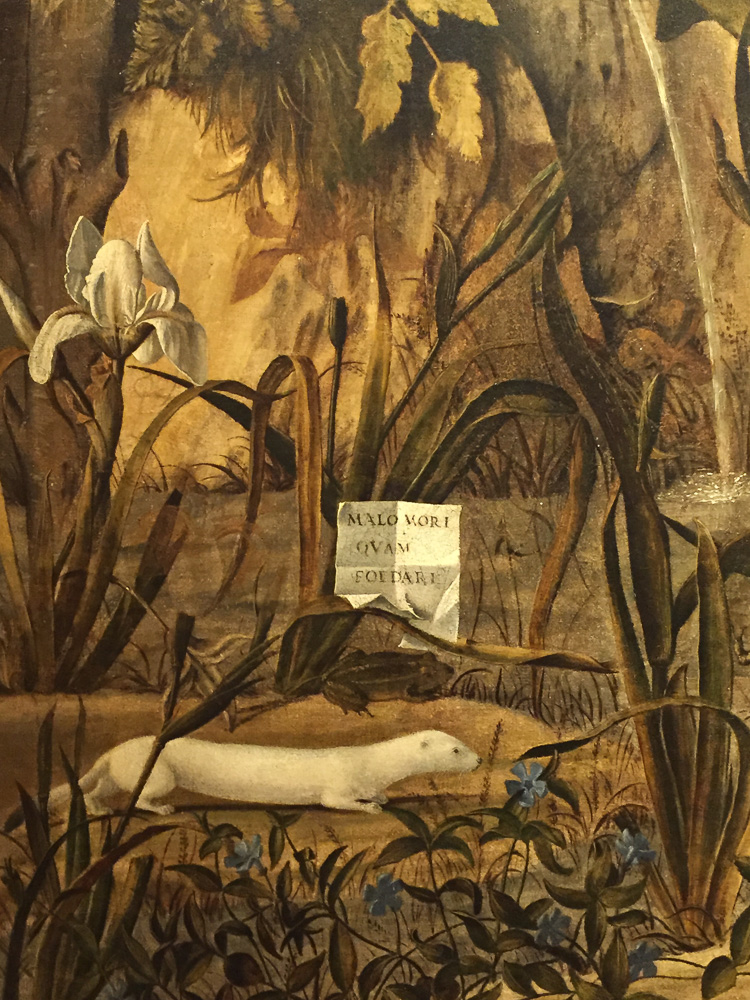

Young Knight in a Landscape

oil on linen, 1505

HOW DID I NOT KNOW THIS PAINTING EXISTED UNTIL I SAW IT JUST NOW??

This is amazing. I stood in front of it for 45 minutes at least, and still didn’t absorb all of it. It’s huge, for one thing – 218.5 x 151.5 cm. If you want to see it in more detail, the Thyssen-Bornemisza website has the ability to zoom in on high resolution images – here.

The piece of paper by the ermine says, “MALO MORI / QUAM / FOEDARI”, which translates to “better to die than be defiled”. That, according to the museum’s information, was the motto of the Order of the Ermine. No one has yet figured out who this knight is, but they think he probably belonged to that Order.

I can’t even describe all the details painted in the flowers and foliage. Little bugs, tiny rocks, dozens of types of plants. Then the dogs, and the birds, all the birds! The falcon and the white ibis (if that’s what they are) fighting in midair… ??

He’s carrying letters in his codpiece!! What on earth does that mean? Is it just a handy place for guys to keep stuff?

The horse is beautifully drawn, but… are his ears docked? Did they do that to horses back then? Why? The docking of tails once had a practical reason at its foundation, but I can’t imagine how docked ears could be an advantage. I found a scholarly article about the mutilation of horses in Medieval England, but it refers to acts performed by enemies, for reasons of retaliation, subjugation, and humiliation… not aesthetics.

The funny young boy on the horse doesn’t look very knight-like. The artist is playing a game there, making it look like the peacock is standing on the boy’s helmet, when really he is standing on the wall behind him. And then the peacock’s beak just touches the sign-horse’s hoof. Carpaccio is messing with our sense of space just like a modern master. And oh, what a beautiful chain of positive and negative shapes it creates…

In the Accademia in Venice, the cycle of incredibly detailed paintings about St. Ursula and her 10,000 Virgins is also by Carpaccio.

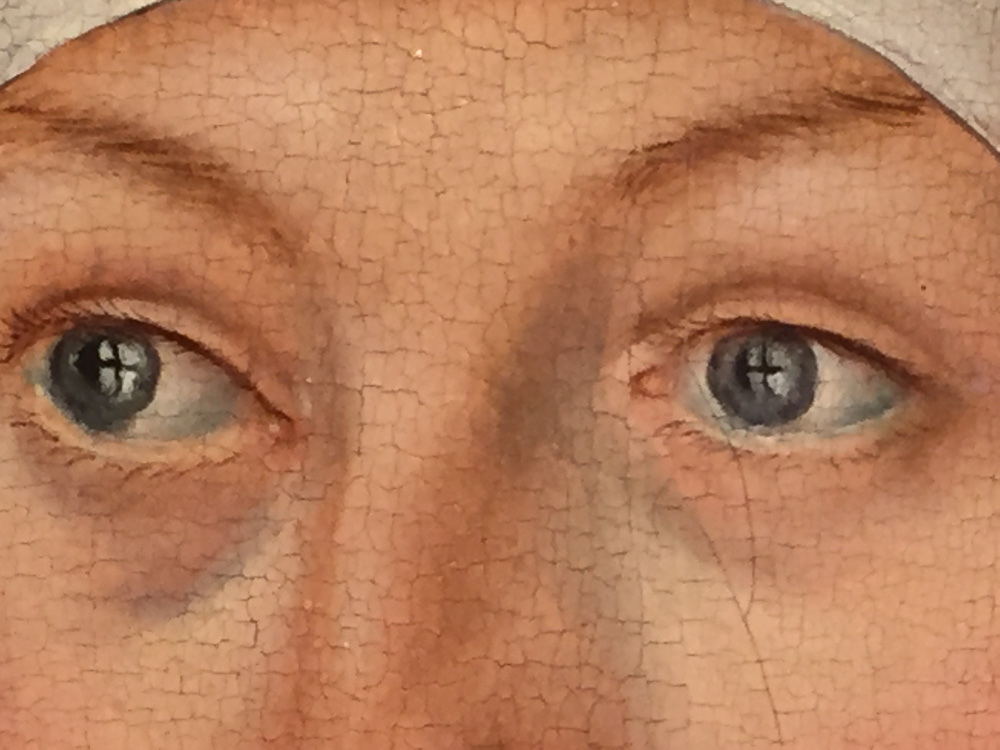

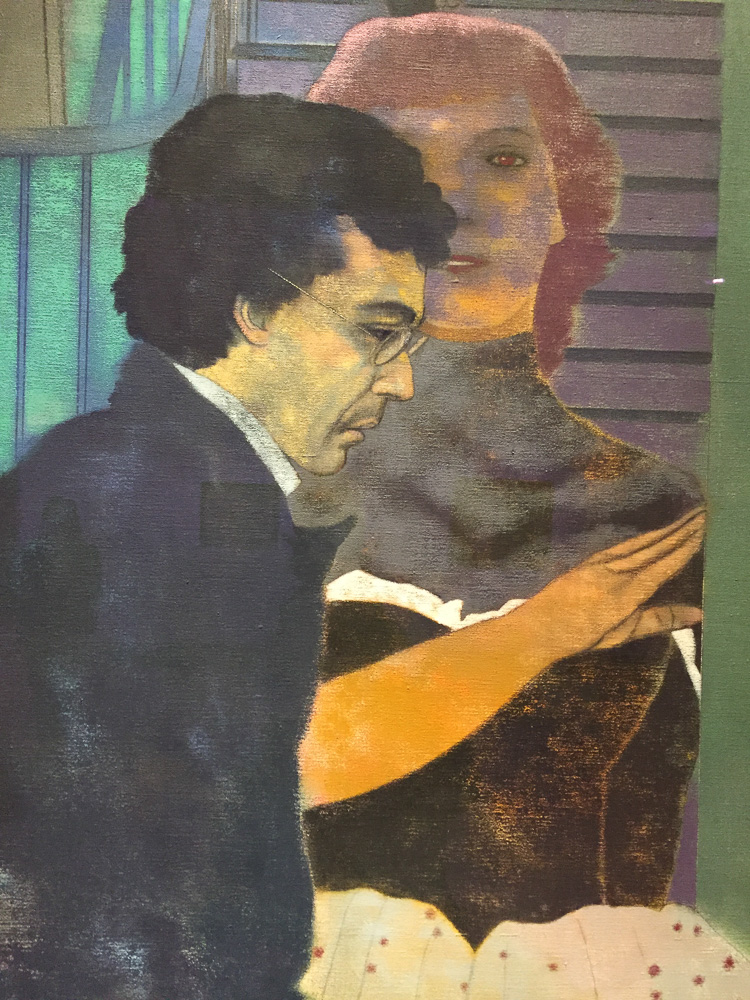

Sebastiano del Piombo

Portrait of Ferry Carondelet with his Secretaries

oil on panel, 1510-12

The best part of this painting is the “secretary” lurking in the background – partly because it’s narratively interesting, but mostly because painting a figure and then glazing it down to transparency like that takes a lot of skill. One time I painted a pumpkin and hid a cat in the back that way. It was a Halloween painting… a bit gimmicky, but someone liked it and bought it.

The second best part of this painting is Carondelet’s eyes. They are most decidedly looking in different directions. Was he slightly wall-eyed, or did the painter just paint them at different times, when the sitter was looking at two different things? That can happen. But I’ve read a lot of Margaret Livingstone, a neurobiologist at Harvard who has written many books on the science of vision. She pointed out that Rembrandt depicted himself over and over again as being slightly wall-eyed, and concluded that he was stereoblind – a condition that causes one to have difficulty seeing the world in three dimensions, a condition which could make it easier for an artist to draw what he sees on a flat surface. All very interesting, but this isn’t a self-portrait, and Carondelet wasn’t an artist, he was a cleric and diplomat. So I guess he was just wall-eyed.

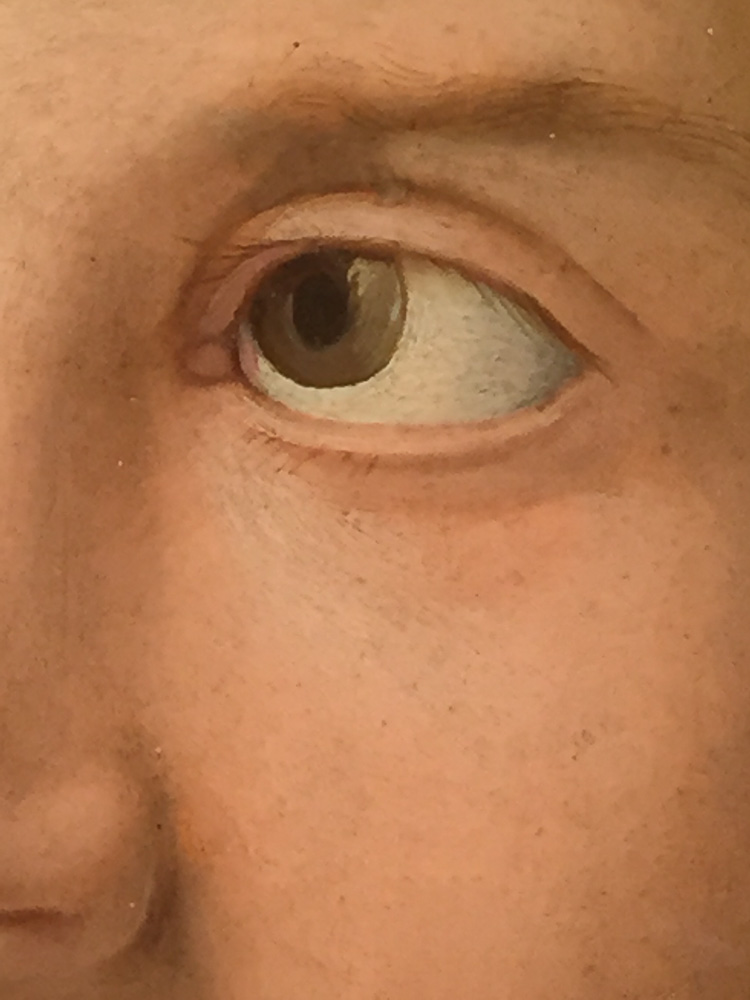

Lorenzo Lotto

Self-Portrait?

oil on panel, date unknown (between 1513 and 1525, perhaps)

I like Lotto very much, especially that green-over-brown background he often uses. I stole exactly this for a portrait I did of my sister.

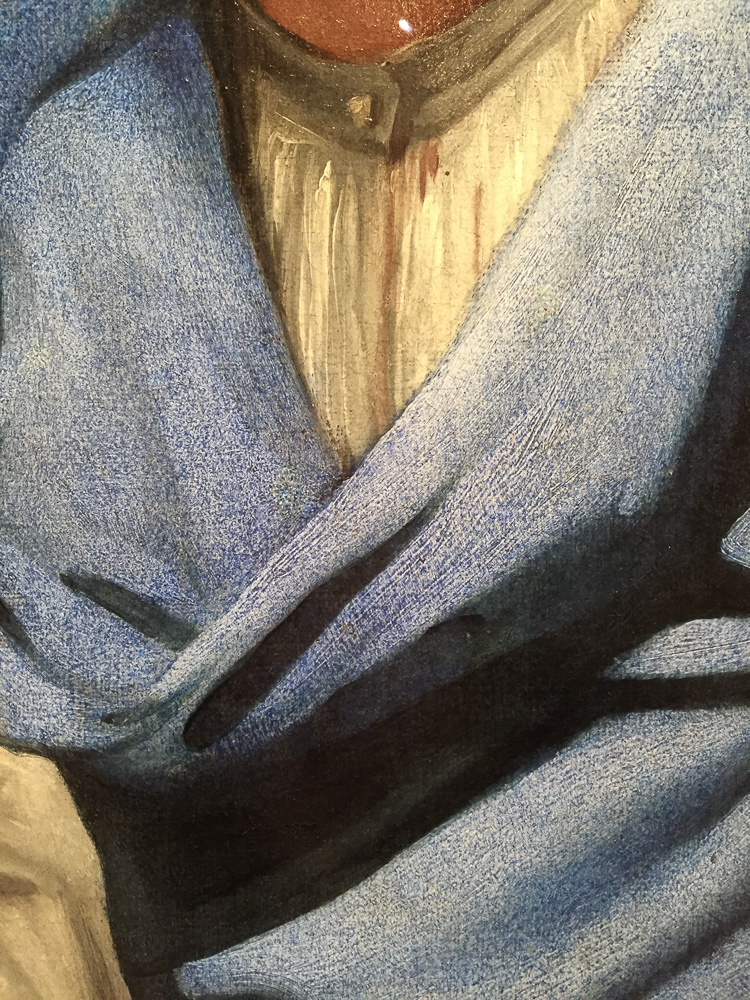

Palma il Vecchio (Jacopo Negretti)

The Virgin and Child with Saints and a Donor (detail)

oil on panel, transferred to linen, 1518-20

What a profile. You can see, as the paint has become more transparent over time, where Negretti changed the shape of the nose. How lightly the Virgin is touching the donor’s head. And above that, a strange, tiny figure in the far-off distance.

Palma il Vecchio (Jacopo Negretti)

Portrait of a Young Woman Known as “La Bella” (details)

oil on canvas, 1518-20

Hands and drapery. Two of my favorite painted things.

Jan Mostaert

The Expulsion of Hagar (detail)

oil on panel, 1520-25

Another story that I had to look up on the Thyssen-Bornemisza website: “According to the biblical account, Sarah, wife of the patriarch Abraham, was barren. For this reason she offered her eighty-six-year-old husband an Egyptian slave named Hagar so that they could conceive a child. Hagar gave birth to Ishmael and from that moment began to look at Sarah with disdain. Sarah, however, also conceived a son by her husband who was named Isaac. On the day that she weaned Isaac there was a great banquet at which Ishmael behaved badly, for which reason Sarah asked Abraham to expel him from their house together with his mother Hagar. This decision was hard for Abraham but he obeyed God’s command to do what his wife had asked him. On the following day Abraham took bread and a bottle of water and gave it to Hagar, taking leave of them both.” Oh, human relationships are complicated, and those polygamous patriarchs were harsh.

Anonymous German, school of Lucas Cranach the Elder

Portrait of a Woman, Aged Twenty-Six (detail)

oil on panel, 1525

I look into this plain German face, and see my own. Eyes for windows.

Barthel Beham

Portrait of Ursula Rudolph

oil on panel, 1528

Fantastic – there is a major drawing error in this face, and yet one hardly notices it.

Marinus van Reymerswaele

The Calling of Saint Matthew (detail)

oil on panel, 1530

oh books books books books books, bundles of paper, soft leather covers, handwritten letters.

Joos van Cleve

The Infant Christ on the Orb of the World

oil on panel 1530

I photographed this painting for my friend, Scott Belville, who also makes paintings of babies balancing on globes.

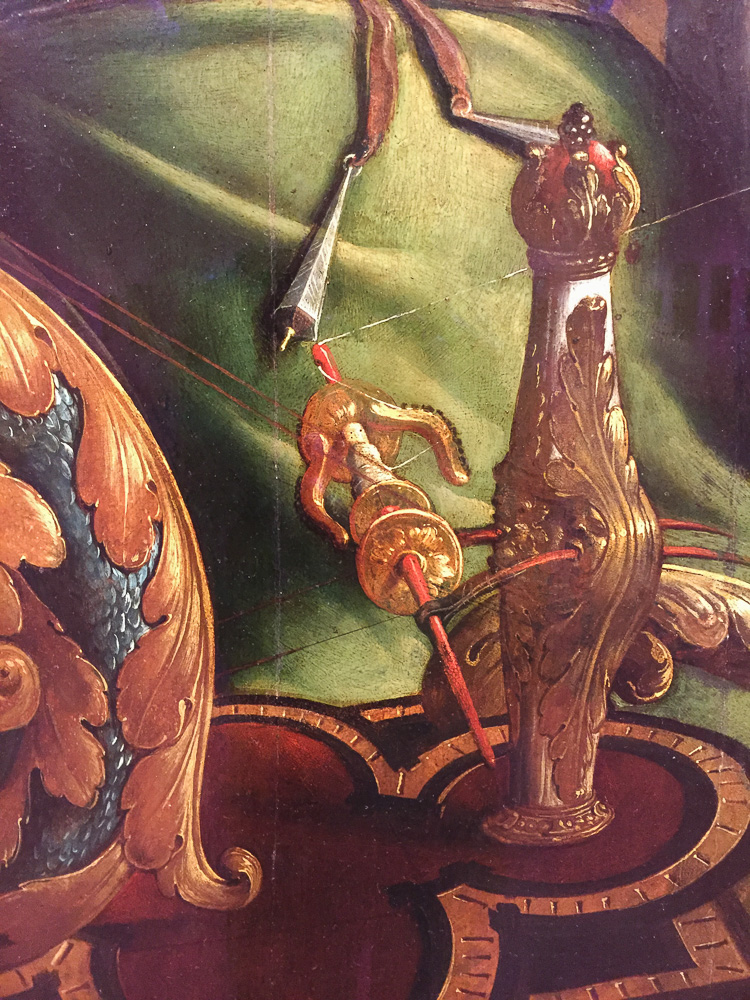

Maerten van Heemskerck

Portrait of a Lady Spinning

oil on panel, 1531

Oh man, this one I LOVE. I had never seen it before, and don’t know anything about the artist. The subject is giving us such a saucy look. The hands, the foreshortening, the golden details on her fancy spinning rig, the fineness of the thread, the luscious drapery of her gown, all of it, just gorgeous.

Bronzino

Portrait of a Young Man as Saint Sebastian

oil on panel, 1533

I mean, have you ever seen such a well-painted male nipple?? I never have. And he seems completely unfazed by the arrow sunk deep into his thorax, which you might not even have noticed, it’s so secondary.

Bronzino is a strange painter. So realistic and so not-realistic at the same time. Excellent drawing, but it verges on the cartoony, perhaps because of the strong outlines. He was a second-generation Mannerist (student of Pontormo) so the messed-up anatomy of this figure’s left upper arm is explicable. And yet, those hands… perfect.

Hans Cranach

Hercules at the Court of Omphale (detail)

oil on panel, 1537

The story of Hercules and Omphale is one that I only learned recently, when I saw Tommaso Solari’s stunning sculpture of Omfale in the Capodimonte in Naples and wondered who she was. I had never heard of her, but at first assumed she had something to do with the omphalos, or navel of the world, that we see in the Roman forum. But no, it seems the two things are not related at all…

Omphale’s story has many variants in Greek mythology. She was, perhaps, the queen of the Kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor, and Hercules was sent by the Delphic Oracle to be her slave for one year as punishment for his murder of Iphitus. It was shameful for Hercules to serve an Oriental woman in this fashion; he was forced to do women’s work and even wear women’s clothing. And yet, in the artistic depictions of this subject I’ve seen, Hercules seems to be rather enjoying it… Omphale took the skin of the Nemean Lion away from him and wore it herself, and carried his club. After his year of servitude was completed, Omphale freed Hercules and took him as her husband. They had many children together, one of which was Tyrrhenus.

Since learning to identify the story I’ve seen more versions of it in art, and they’re all wonderfully full of the themes of gender role reversal, cross-dressing, male-female power relationship inversion, and… love.

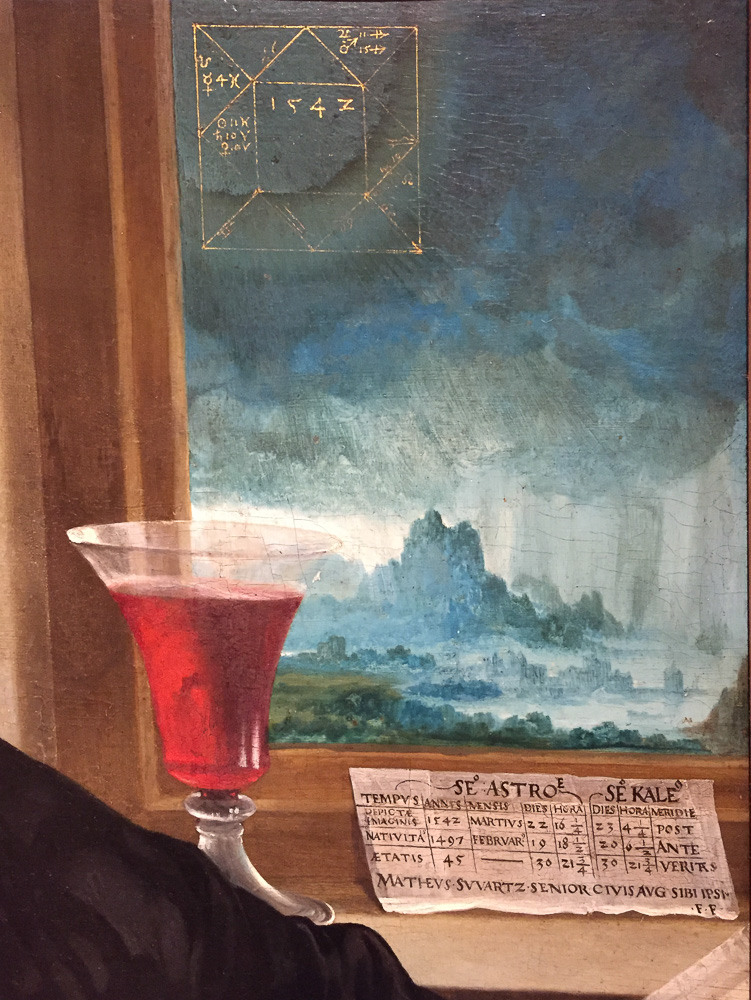

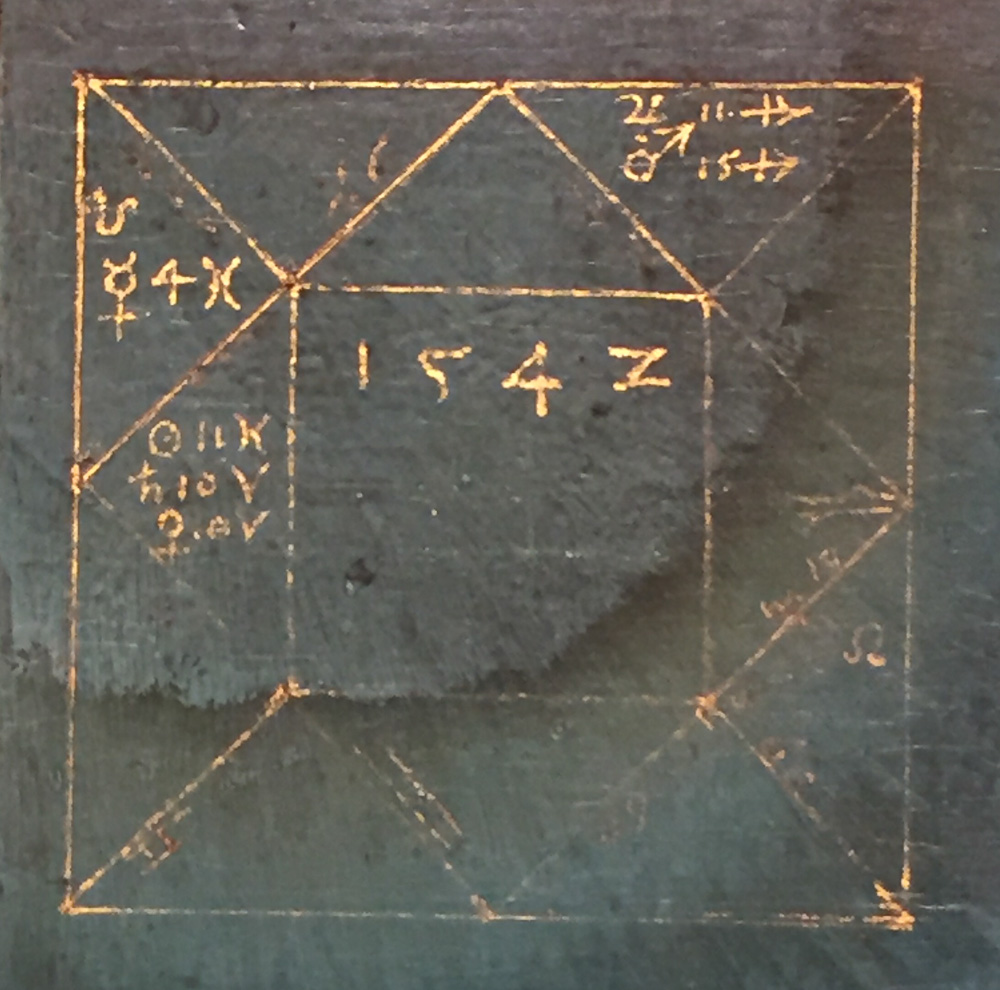

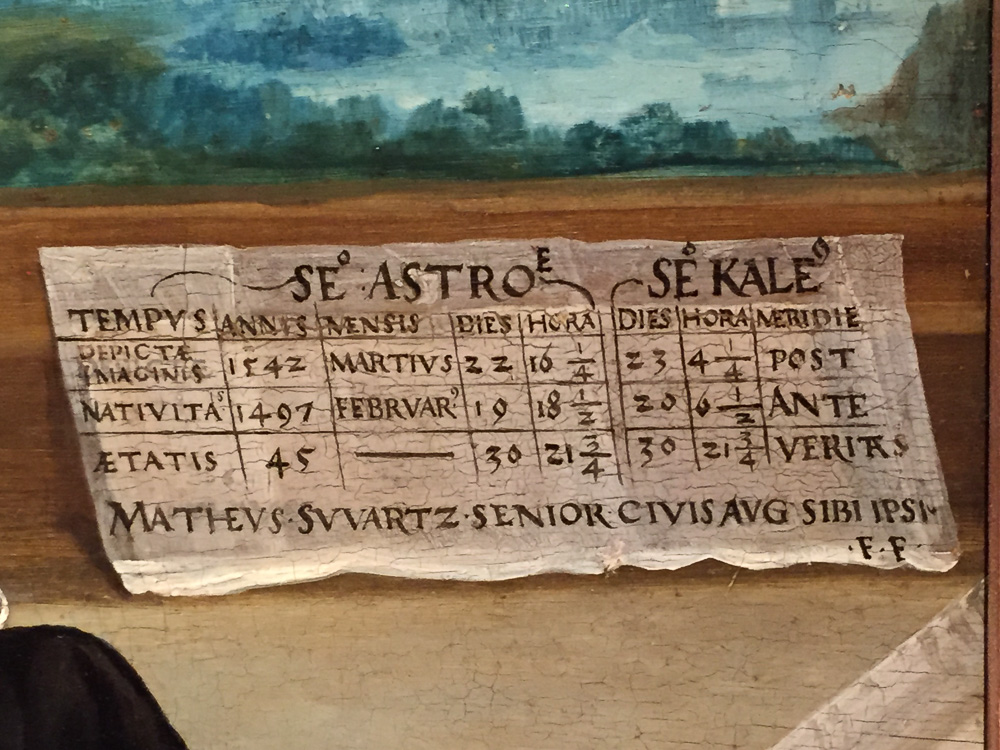

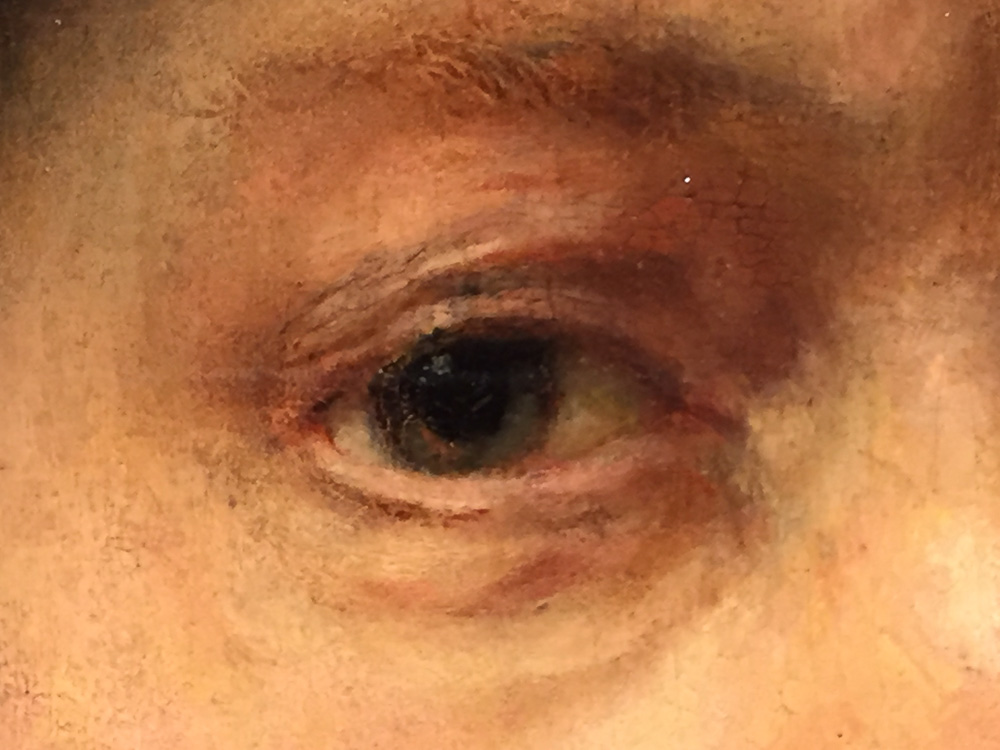

Christoph Amberger

Portrait of Matthäus Schwarz

oil on panel, 1542

This Matthäus Schwarz character has a kind face, with mis-matched eyes and a fine bulbous nose. I love paintings with obscure astrological and mathematical references in them, such as the portrait of Luca Pacioli at the Capodimonte museum. Schwarz wasn’t a scientist or mathematician or astrologer, though, he was an accountant who wrote a book describing the most important pieces of clothing that he wore throughout the course of his life. Fascinating.

Ridolfo Ghirlandaio

Portrait of a Nobleman of the Capponi Family (detail)

oil on panel, 1555

Another hefty individual, but this one I don’t feel much sympathy for. Mr. grumpy-pants. Looks like an asshole, actually, with the capacity for cruelty. But in any case, still pretty divinely painted, which is no wonder, as it’s a Ghirlandaio.

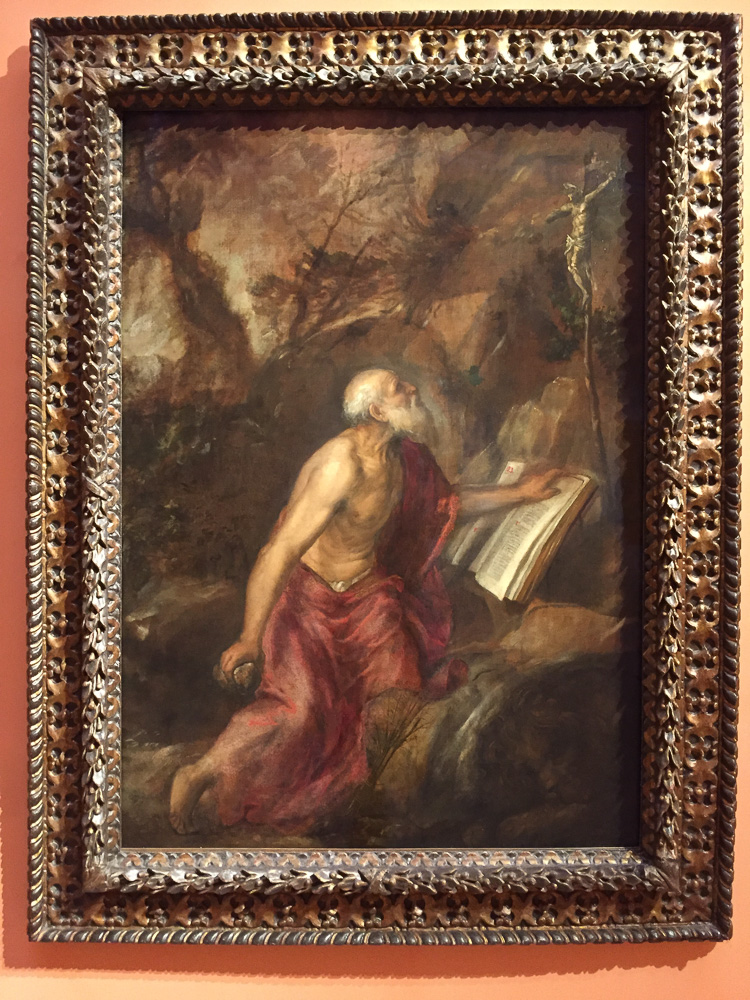

Titian

The Penitent Saint Jerome

oil on canvas, 1575

I try to like Titian, I really do. Sometimes he moves me… but not here.

Caravaggio

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

oil on linen, 1598-99

I wasn’t expecting to see a Caravaggio I didn’t know about… yet another instance today of walking into a room and feeling my jaw drop.

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary (details)

oil on panel, 1609-10

No words.

Anton van Dyck

Christ on the Cross (detail)

oil on canvas, 1627

The transparency of the legs… the efficiency with which the forms are suggested with semi-opaque paint that barely covers the underpainting… the lack of definition at the edges of the form… and yet it all comes together to seem so solid and present.

José de Ribera

The Pietà

oil on canvas, 1633

Look at the dead color of Christ’s hand, the awkward heaviness of his limp body, the accidental grace of his feet… that is some very fine observation of nature.

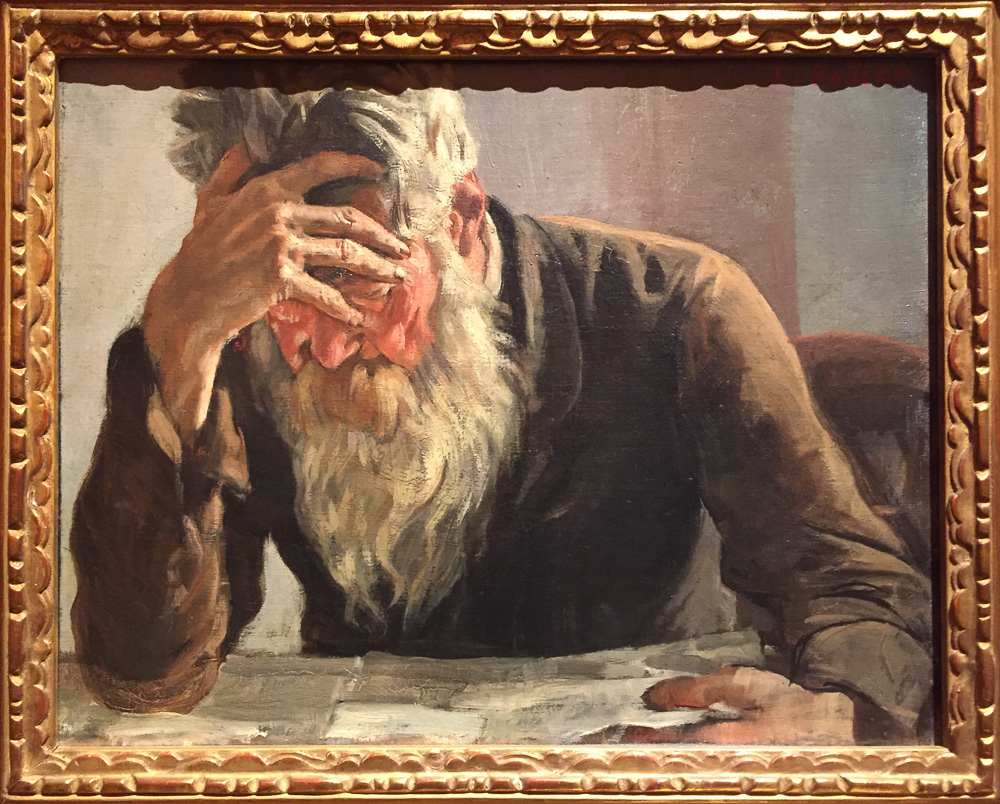

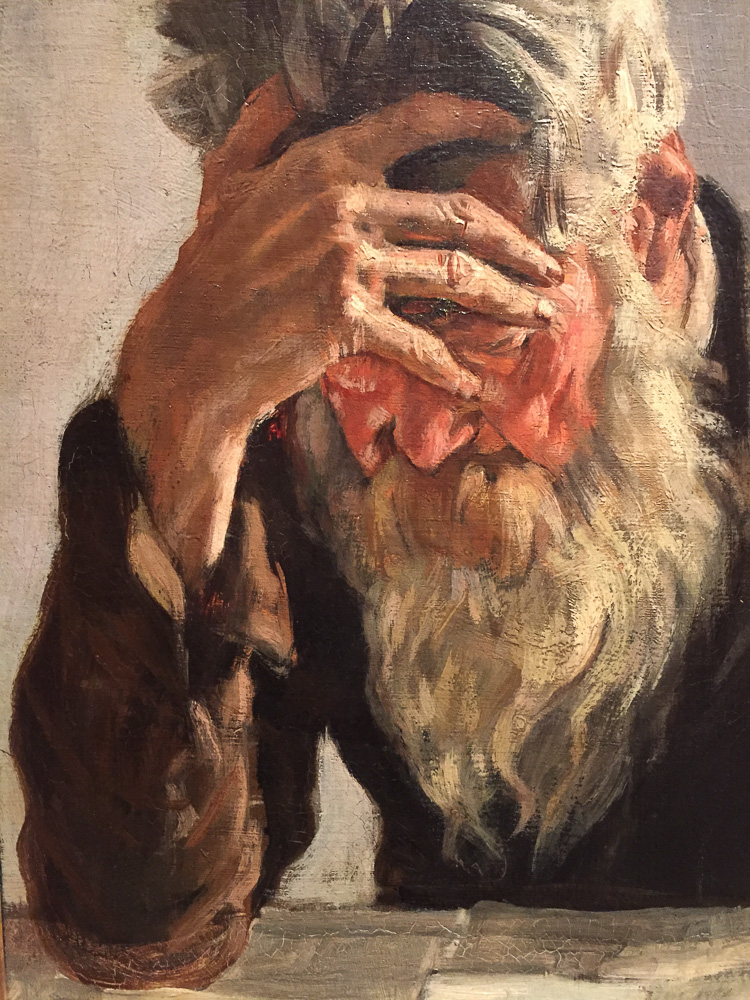

José de Ribera

Saint Jerome in Penitence

oil on canvas, 1634

More incredible painting from Ribera, worthy of long study. The wrinkles of loose flesh over the bones of the hand, the folds of sagging flesh in the ribcage, armpit, and elbow of the saint, the creasing skin around the eyes – all sculpted with a solidity of paint, almost as if carved. This one runs circles around the Titian of the same subject that we just saw.

Francisco de Zurbarán

Saint Casilda

oil on canvas, 1635

Casilda (martyred in 1087) was the daughter of an Arab king, who converted from Islam to Christianity. When caught taking food to her father’s Christian prisoners, a miracle transformed the food hidden on her person into roses, which are now her attribute.

Bernardo Cavallino

The Drunkenness of Noah and Lot and His Daughters

oil on canvas, 1640-45

Two paintings about men getting drunk. The story of Lot’s daughters is one of the most effed-up things I’ve ever heard – they definitely didn’t teach us that one in United Methodist Sunday School.

Rembrandt

Self-Portrait Wearing a Hat and Two Chains

oil on panel, 1642-43

Again, there are just no words. Trying to understand how the paint sculpts the folds around the eyes, and how all that mess of soft brushwork somehow comes together to make a nose and mouth.

Frans Hals

Family Group in a Landscape (details)

Oil on canvas, 1648-48

Frans Hals is an amazingly economical painter. There is so much speed and assurance in his brushwork, and from a few paces back it doesn’t seem that any details have been sacrificed. Only up close do you realize how much he’s fudging it. The mundane title of this painting totally belies how much complexity exists in the relationships between these five people. The inclusion of the slave boy, right in the middle of the family group, is intriguing. His shadowed figure is visually pushed to the background, and yet he’s the only one making direct eye contact with the viewer.

Ferdinand Bol

Young Man in a Feathered Cap (detail)

oil on canvas, 1647

Not a show-stopper, but a well-done example of good indirect painting.

Michiel Sweerts

Boy in a Turban Holding a Nosegay

oil on canvas, 1658-61

This one is all about that blue drapery. How was it done? It seems to me that a blue glaze was applied on top of a neutral underpainting, but was then wiped back dramatically. There is no opacity whatsoever in the highlights of the blue cloth. Unlike the white shirt, which has the normal amount of thick-thin contrast.

I wonder about the psychological state of this boy model, who seems to be holding back tears, lower lip quivering, while obediently wearing his costume and holding his nosegay for the painter…

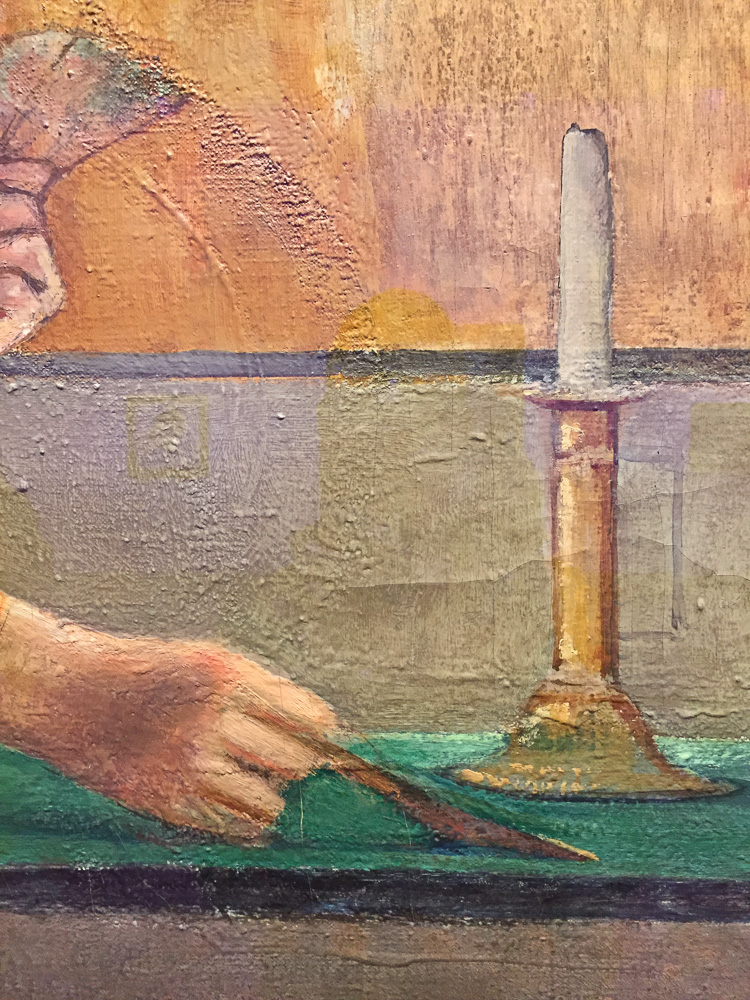

Gerrit Dou

Young Woman with a LIghted Candle at a Window

Oil on panel, 1658-65

How hard must it have been to observe and paint a single-candle light source in an age before artificial lighting and photography? I always wonder, how did these artists see well enough to paint in the dark? There are all kinds of theories about the theatrical tricks Caravaggio may have used…

Luca Giordano

The Judgement of Solomon (details)

oil on canvas, 1665

Look at the fabric, the folds of it, the twists of it created with paint as if paint were sculptural, and the old woman’s skin gathered just like the folds in her turban.

Nicolaes Maes

Portrait of a Lady

oil on canvas, 1667

All the beauty of this sitter is contained in the hand holding the watch…

Murillo

The Virgin and Child with Saint Rose of Viterbo (detail)

oil on canvas, 1670

Such a pretty, humble young saint, with a completely trusting face. I’m glad she’s got the Virgin Mary looking out for her, because it’s a hard world out there.

Caspar Adriaansz. van Wittel (a.k.a Vanvitelli)

Piazza Navona, Rome

oil on canvas, 1699

This one made my list because it’s just fun to see what Navona was like in 1699! A lot muddier, apparently. Hard to believe those big fancy fountains were there without any pavement.

Giambattista Piazzetta

Portrait of Giulia Lama

oil on canvas, 1715-20

The languid… scorn?… in that gaze… and the shape and color of the shadow that defines her eyes and cheek, so far from black…

Giulia Lama (1 October, 1681 – 7 October, 1747) was an Italian painter, poet, mathematician, lace-maker, and inventor active in Venice. She was known for her plain appearance; in a letter written by the Abbé Conti to Madame de Caylus in March 1728, the Abbé remarked, “It is true she is as ugly as she is intelligent, but she speaks with grace and polish, so that one easily pardons her face…She lives, however, a very retired life.”

My heroine.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

Still Life with Pestle and Mortar, Pitcher, and Copper Cauldron

Oil on canvas, 1728-32

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin

Still Life with Cat and Rayfish

Oil on canvas, 1728

I’ve liked Chardin since I was a student; he was particularly good at portraying metallic surfaces. His messed-up cats appeal to me, too.

Giambattista Tiepolo

The Death of Hyacinthus

oil on canvas, 1752-53

I love Tiepolo, how he dashes off satiny fabrics, how he draws with the brush while painting, leaving all those beautiful calligraphic lines. Just look at that blue ribbon wrapped around the racket handle. Luscious paint. And the story of Hyacinth and his lover Apollo… epic.

Claude Joseph Vernet

Night: Mediterranean Coast Scene with Fishermen and Boats (detail)

oil on canvas, 1753

A painting with two light sources: one of the hardest value structures to organize.

Théodore Géricault

Horse Race (detail)

Oil on paper, attached to canvas, 1817

Such pretty horse feets

Eugène Delacroix

The Duke of Orléans Showing His Lover

Oil on canvas, 1825-26

This is the most disturbing painting I have seen in a very, very long time. Those glass objects set up under the baldachin in the background are the type carried on voyages by the rich and powerful of that time, to be put on display at their host’s residence, in order to advertise their own power and wealth. Meetings between great powers would fill enormous halls, with each head of state banqueting at his own table, with his own retinue, and behind him a wall of goblets, platters, and other objects of gold, silver, glass, and gems, with the heraldic crests of all the families with which that leader was aligned. In this painting, the proximity of the four-poster bed to the display of cups makes me think that this humiliated woman is nothing more than another object put on show by the Duke to impress his political peers. Not unlike the horse in Géricault’s painting, I suppose… but note that the horse is unbridled (i.e. free) and full of dignity. This poor woman isn’t even given the compliment of having her entire body and her face (i.e. her individuality) revealed – she has been reduced to nothing more than her sex.

Those were my thoughts in the gallery, when I first saw this painting. Upon further research I learned that the painting has a literary source, and the three characters are the participants in a historic love triangle. The Thyssen-Bornemisza website says, “…a passage in the Histoire des ducs de Borgogne by Barante, republished in 1824… describes how the Duke of Orléans displayed the naked body of his lover Mariette d’Enghien, wife of his former chamberlain Aubert le Flamenc, to her husband, concealing her face. Her husband failed to recognize her… another more detailed [text] has been mentioned, which the artist may have used as his source. This is Les vies de dames galantes by Brântome, republished in 1822, two years before Barante’s text. In Brântome’s description the Duke of Orléans shows his lover to her husband, concealing her face with a sheet.”

Not sure that any of this changes how I feel about this painting. Does Delacroix have any compassion for Mariette? Or is he enjoying the position of voyeur, just like Aubert le Flamenc, and just like the audience that the painting was made for? Even if Mariette was a “willing” participant in these romantic intrigues, did she really have any control over her fate?

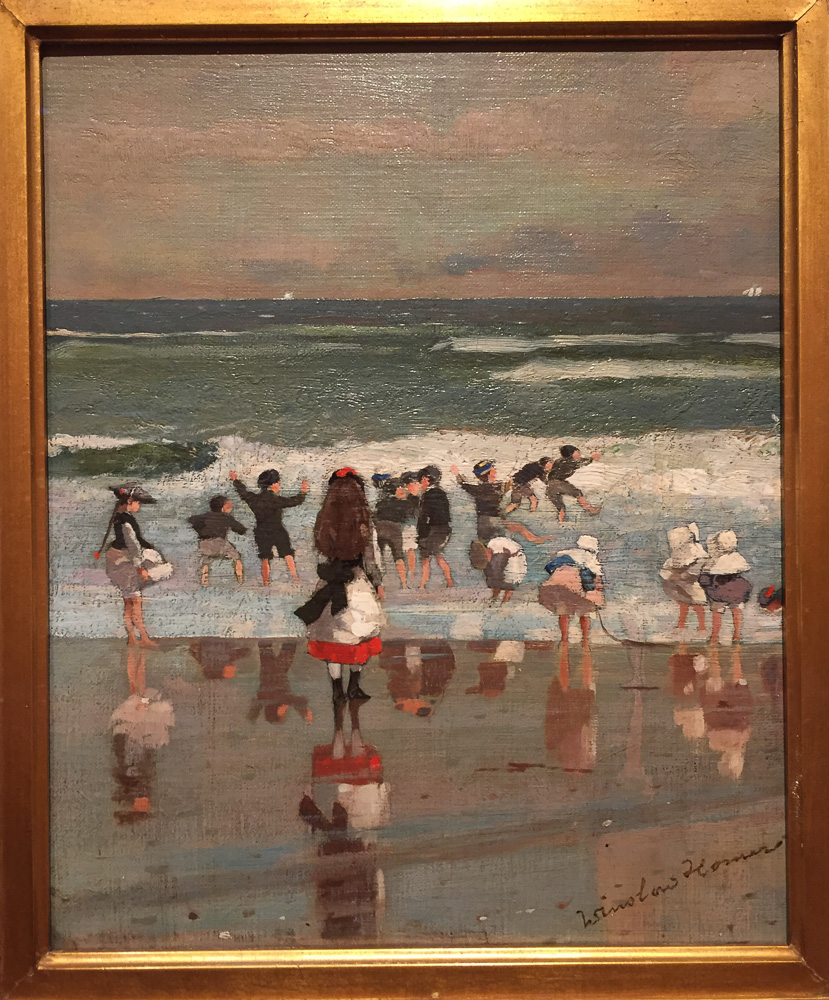

Winslow Homer

Beach Scene

oil on canvas, 1869

I’ve always liked Homer. Not for the “Americanness” of his scenes, but for the simple brush-shapes of color with which they are painted. The girl in the red skirt is a perfect example. I had a teacher once who talked incessantly about “pieces of paint” and finally I’m understanding what he meant.

Winslow Homer

Portrait of Helena de Kay

oil on panel, 1872

Another Homer, this one fraught with delicious pathos. The composition is perfect.

John George Brown

Tough Customers

oil on canvas, 1881

Ladies’ Victorian button boots might be a fetish of mine.

Brown has captured without words the complex social dynamic between these young characters: the boys who each secretly want this girl to give him her favor, but have no idea how to interact with her, and are too afraid to try anything alone, so they gang up to tease her while she is working. She, with jaw set, stoically endures their immature jibing while thinking how she would like to kill them all. Little knowing that they only want her to love them.

John George Brown

Dress Rehearsal (detail)

oil on canvas, 1884

It’s the socks, and the raggedy pants, and how succinctly both are painted…

Edgar Degas

At the Milliner’s

pastel on paper, 1882

When I entered graduate school, I naïvely believed that Edgar Degas was just a wifty pastellist of ballerinas. Then I got a book about him from the IU Art Library and my mind was blown open. First and foremost, his compositions are highly complex and were innovative for his time, influenced by Japanese prints. His embrace of the early science of photography, and how he used it in service of his art, was instructive for someone who had always been told that painting from life was the only valid form of observation. And finally, there is nothing wifty about pastels, when used the way he used them. Seeing this piece in person was very exciting for me.

John Singer Sargent

Venetian Onion Seller

Oil on canvas, 1880-82

An early Sargent, yet his signature confident brushwork is already mature. Look at how he abbreviated the view of Venice outside the window!

Ferdinand Hodler

The Reader

Oil on canvas, 1885

I recently bought a book about Hodler because I knew so little about him, but had seen a few paintings around that were interesting. I like this one very much, especially how that hand is painted.

John Atkinson Grimshaw

A Moonlit Evening

oil on cardboard, 1880

This is a new painter for me. Based on the two paintings by him in this collection (the other one follows), Grimshaw seems to be very good at creating atmosphere, especially cold dark foggy night atmosphere, with a second warm light source beckoning us home, into the painting. I certainly don’t want to be standing out here in all this slick shiny mud, I’d much rather be inside that well-lit dining room, looking back out into the night and wondering if the maid was only a ghost.

John Atkinson Grimshaw

“Canny Glasgow”

oil on canvas, 1887

Like Vernet’s nighttime scene we saw earlier in the museum, and like Grimshaw’s other painting in this collection, this painting has two light sources. One is cold, misty, dim, natural; the other is warm, bright, artificial. To put both into one painting takes tremendous skill. And then on top of that, to paint shiny wet cobblestones, and a hazy sunset, and glowing red lanterns on the dock… oofah.

William Merritt Chase

In the Park (a By-Path)

oil on canvas, 1889

Next time I need to paint the walls of Cortona, I’m coming back to this painting.

Henri-Edmond Cross

Women Tying the Vines (detail)

oil on canvas, 1890

It’s all about the color in the shadows…

Maurice Brazil Prendergast

The Race Track (Piazza Siena, Borghese Gardens, Rome)

Watercolor on paper, 1898

I know very little about Pendergast, certainly didn’t know his middle name was “Brazil”. This painting tickled me for two reasons: 1) it depicts the Piazza Siena in the Villa Borghese park in Rome, a space I pass through several times a year, but have never seen so populated as this, and 2) I aspire to make more and better watercolors, especially while traveling. I’m learning a lot from looking at this one.

John Singer Sargent

Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland

oil on canvas, 1904

I do love Sargent, but the colors of her dress are pretty awful.

This is a good opportunity to say also that the frames on the artworks in the Thyssen-Bornemisza have as much character as the works themselves, sometimes even more. Never before in a museum have I noticed the frames so much, or felt so often compelled to include them in my photographic records of the artworks that struck me.

John Frederick Peto

Toms River

oil on canvas, 1905

I photographed this one for Scott Belville, as well… where does the painting end, and the frame begin?

James Ensor

Teatro de máscaras

oil on canvas, 1908

This one, too, is all about the frame. Like with the Peto above, where does the spectacle end and the stage begin?

Childe Hassam

The French Breakfast (detail)

oil on canvas, 1910

How does he keep it all together, how does he coordinate all the colors and brushstrokes to make sense? I mean, LOOK at that salt shaker!! This photo reproduces an area of only a few square inches in reality.

Childe Hassam

Plaza de la Merced, Ronda (details)

oil on panel, 1910

I’m so literal… I always think first about the subjects of paintings. What’s the story, I want to know. But I’m getting wiser, more experienced at looking. I couldn’t care a fig for the subject of this painting, but I could study the way it is painted for hours. The balcony is like the salt shaker in the previous painting. How did he reduce it down to its essential elements so effectively? Abstraction is such a mystery to me.

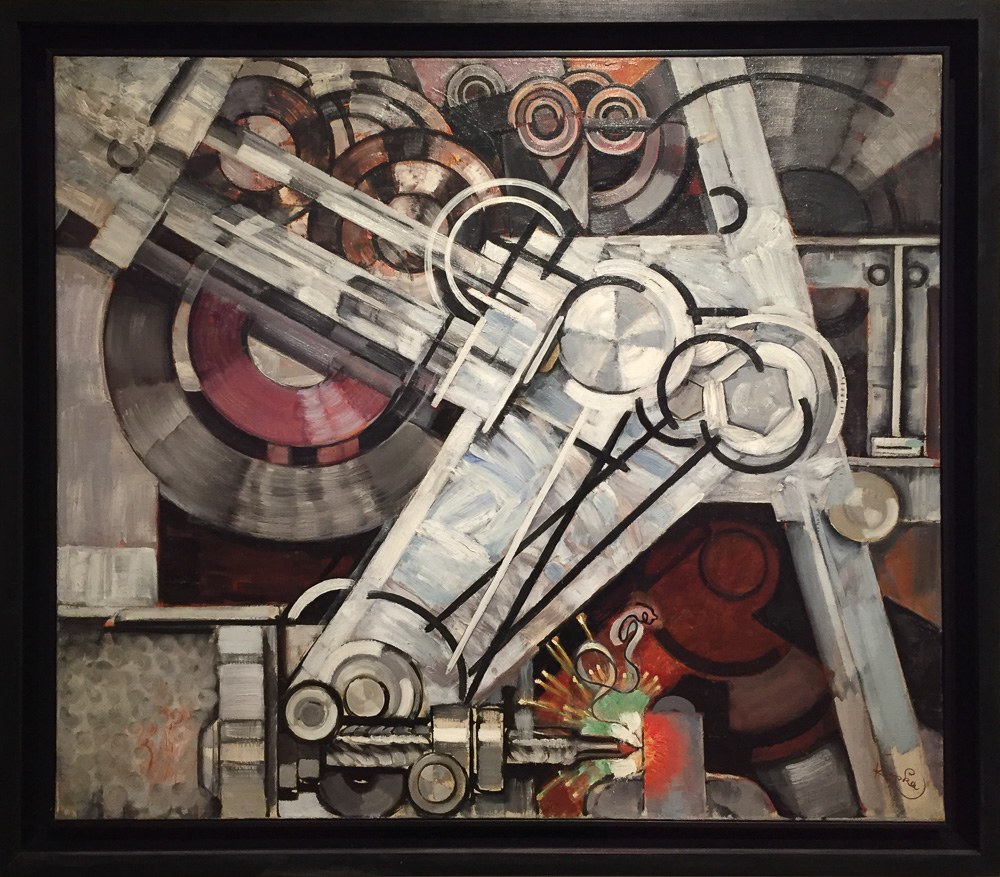

František Kupka

Study for the Language of Verticals

oil on canvas, 1911

This one I love, very much. Beautiful colors, beautiful pieces of paint, solid and dimensional, like a hanging curtain, each tassel swinging and knocking and making the whole curtain move. Great title, too.

František Kupka

The Machine Drill

oil on canvas, 1927-29

Another one by the same artist, full of banging movement. I like it better than Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which it makes me think of… (both artists were involved in the Cubism movement for a while).

Natalia Goncharova

The Forest

oil on canvas, 1913

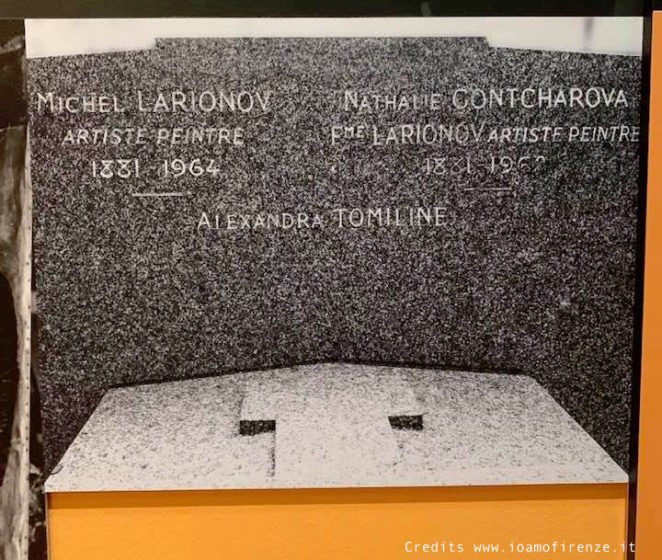

Palazzo Strozzi in Florence just had a big show dedicated to Natalia Goncharova, which introduced me to this artist I never knew about before. She was one of the founding members of the Russian avant-garde and cubo-futurist movements, and later she and her life-partner, fellow Russian artist Mikhail Larionov, developed a painting style they called “Rayonism”, of which I think this painting in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection is an example. She also worked as a graphic, costume, and textile designer. Goncharova and Larionov had a very interesting relationship; they were together their entire lives but only married at the very end, for reasons having to do with the inheritance of their artistic legacies. During their emotional and creative partnership, they spent time away from each other in pursuit of their own interests, and both had other long-term love affairs with individuals who became part of their shared domestic sphere. After the couple moved to Paris, Goncharova found a soul-mate in Orest Ivanovich Rosenfeld, whom she met in 1917; during WWII he was sent to a concentration camp despite Goncharova’s attempt to save him. He survived and married another woman after the war, but always remained a friend to Goncharova and Larionov. In Paris, Larionov dallied with some dancers (he and Goncharova were designing sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes at the time) then formed a long-term relationship with Alexandra Tomilina, who moved into an apartment below theirs and worked as their secretary and later, as they grew elderly and infirm, their housekeeper, cook, and caretaker. After Goncharova died, Larionov married Tomilina, but again, only for legal reasons: so that she could inherit both artists’ legacies, which she promised to carry back to Russia for them. Today Goncharova, Larionov, and Tomilina are buried together in a Paris cemetery.

People are so complicated…

Gino Severini

Expansion of Light (Centrifugal and Centripetal)

oil on canvas, 1913-14

Ok, the truth is I’m somewhat ambivalent about the work of Severini, but hey, he’s from Cortona so I had to make a note that I saw this. And this one’s not bad.

Edward Hopper

Girl at a Sewing Machine (detail)

oil on canvas, 1921

Like Homer, Hopper makes the puzzle-pieces of paint, shapes of color and value, click together and miraculously create light.

Victor Servranckx

Opus 30-1922 (Factory)

oil on cardboard, 1922

I took this one for you, Mark, it reminds me of your designs.

Christian Schad

Maria and Annunziata “from the Harbour”

oil on canvas, 1923

Don’t they look gentle and soft? Schad painted these two actresses in Naples.

Otto Dix

Hugo Erfurth with Dog

tempera and oil on panel, 1926

I don’t know how the younger me knew about this painting, but a postcard of it has been on my various walls for years, probably since I was in high school. Imagine my surprise to find the real thing in front of me! One of the best dog portraits of all time. The man-portrait is great, too.

Christian Schad

Portrait of Dr. Haustein

oil on canvas, 1928

Another Schad, so so psychological and compositional and symbolical and meaningful – the best type of portrait.

Giorgio Morandi

Still Life

oil on canvas, 1948-49

I enjoy the subtlety of Morandi’s muted color ranges, but mostly his work leaves me unmoved, wondering what all the fuss is about. I’ll never forget my teacher and study-abroad program leader Barry Gealt nudging me with his elbow in the Morandi Museum in Bologna, pointing out my male classmates having what he called “little orgasms” in front of the paintings after weeks of suffering from what they considered the overly-precise drawing and garish colors of Raphael, del Sarto, Lotto, Ghirlandaio, and the rest of the Florentine Renaissance.

Balthus

The Card Game

oil on canvas, 1948-50

It is deeply reassuring to me that Balthus also took years to complete a painting. He is one of my favorites. Several years ago in Rome there was a large exhibition of his work at the French Academy; he was the Director of that institution for a number of years. But back to the painting: what an exciting game, what a mysterious smile on the girl’s face. She knows she has the cards to beat her opponent.

Joan Miró

The Lightning Bird Blinded by Moonfire

oil on cardboard, 1955

Thinking longingly of what it was like to be whimsical. The texture in the background is also interesting. The title is fantastic.

Max Ernst

Thirty-Three Little Girls Set Out For The White Butterfly Hunt

oil on canvas, 1958

Titles, in fact, are everything.

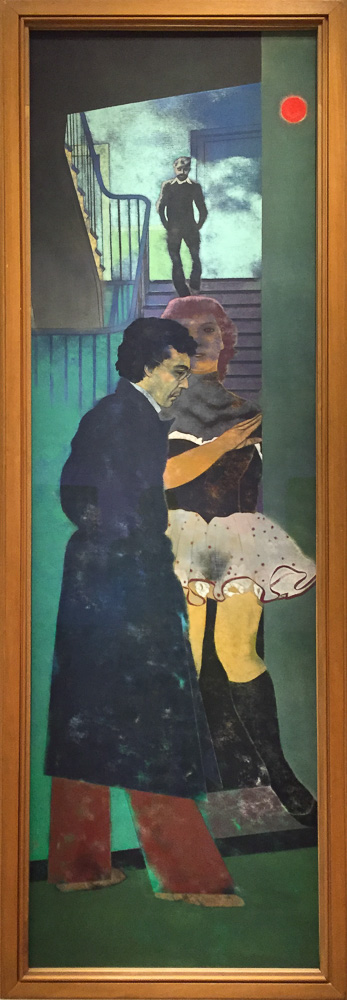

R.B. Kitaj

Smyrna Greek (Nikos)

oil on canvas, 1967-77

Kitaj is a painter that I like very much. #1, his drawing is rock-solid, kick-ass. Sometimes his “paintings” are little more than drawings on canvas. #2, composition, like Degas. #3, he doesn’t overdo the paint-application, keeping it thin, scrubby, and scumbled in most places, and only goes for full opacity where he wants to drop a little bomb. #4, color, well-designed, layered, lots of neutrals interrupted by startling moments of bright intensity . #5, edges, so sharp sometimes, so foggy at others. #6, good titles. Maybe not this painting so much, but what about My Cat and Her Husband?

He killed himself by putting a plastic bag over his head. Nice and simple.

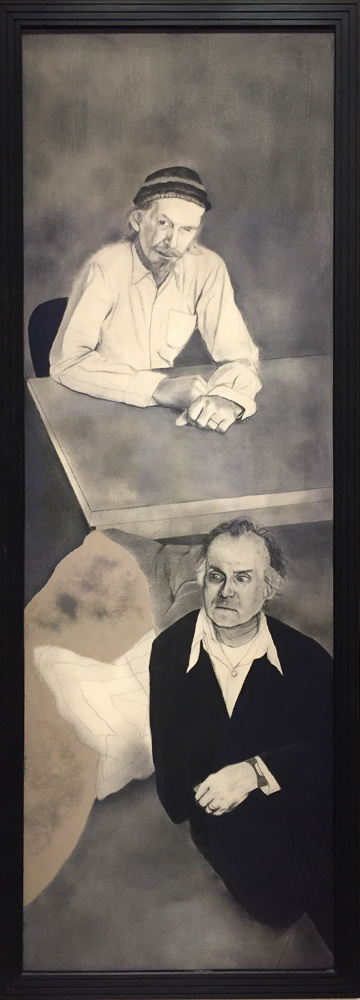

R.B. Kitaj

A Visit to London (Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan)

oil and graphite on canvas, 1977

Composition, drawing, shapes, dark and light, balance, simplicity.

Andrew Wyeth

My Young Friend

Tempera on Masonite, 1970

I started adoring the paintings of Andrew Wyeth back before it was acceptable; in graduate school I would never have confessed that I was looking at him. I was happy to find one of his works in this collection – happy to know I share the tastes of a distinguished collector like the Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza! I feel toasty warm just looking at her bulky woolen sweater and fur hat.

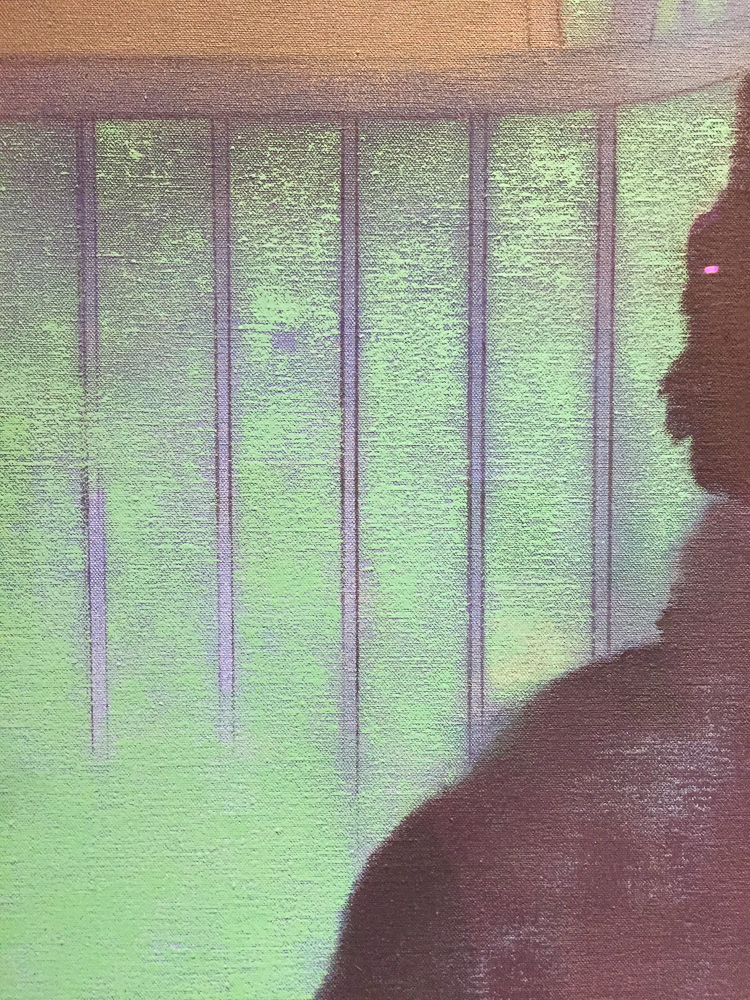

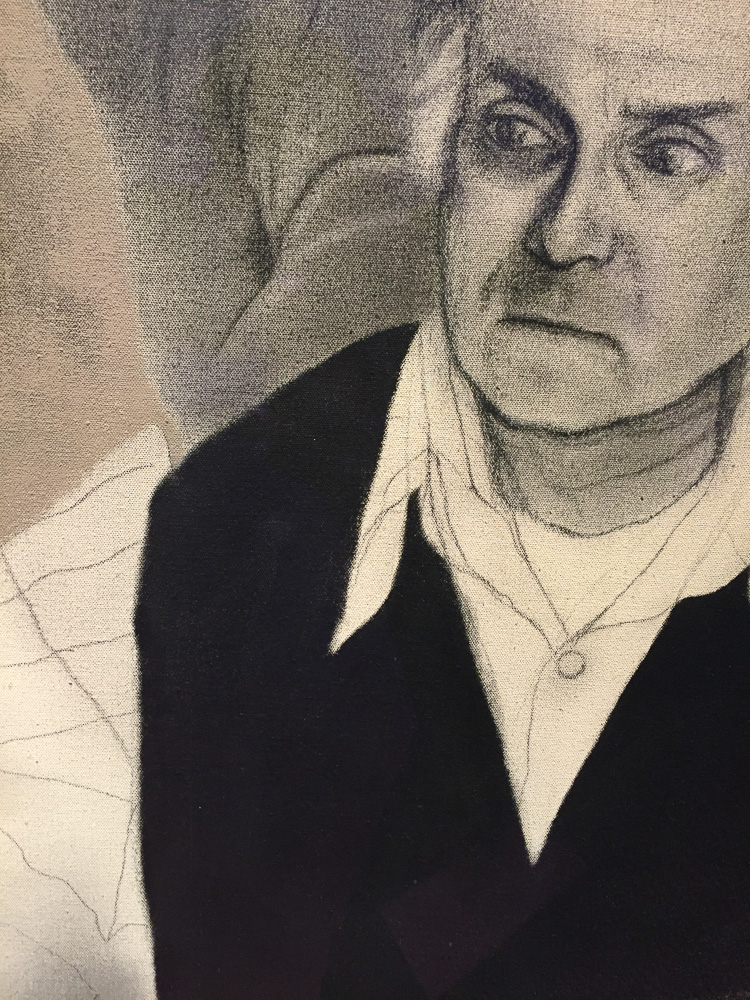

Lucian Freud

Large Interior. Paddington

oil on canvas, 1968-69

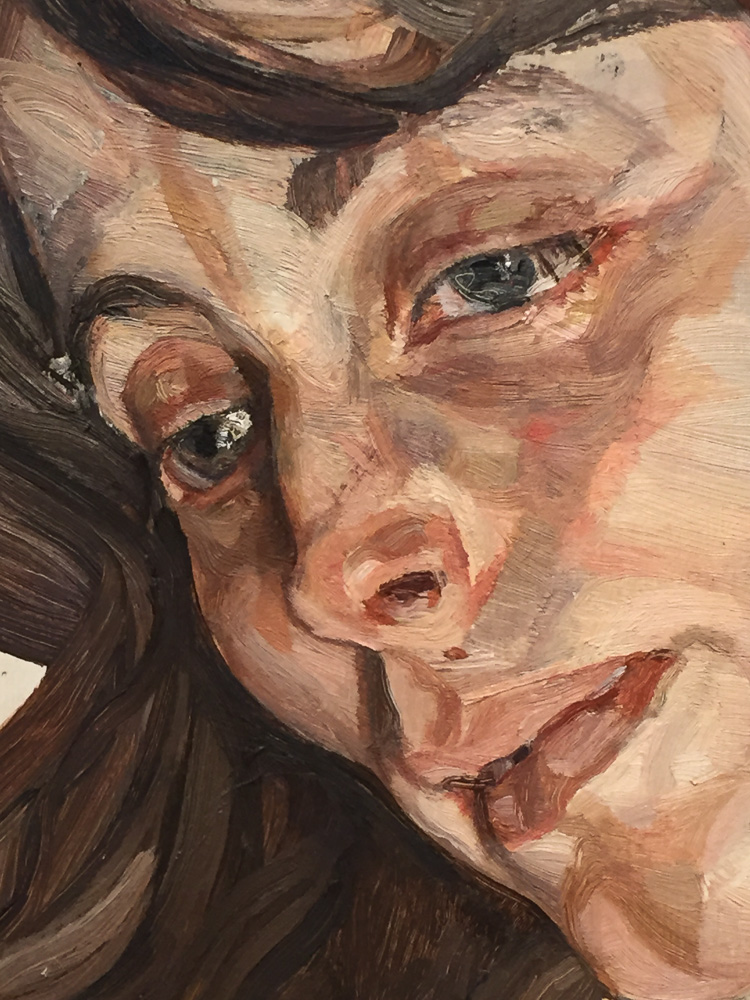

Lucian Freud

Last Portrait

oil and pencil on canvas, 1976-77

How to explain what the paintings of Freud mean to me? They are everything I wish to accomplish in painting. Real, intimate, brutally honest, human. That mole on the neck — he makes it utterly beautiful, a part of the soul of this woman. Beyond the subject, there is simply the sheer physical presence of the paint. My heroes are the ones that make those two things – soul and physical paint – co-exist. There is no need to banish Subject.

Here’s where things get interesting. In the very last room of this amazing museum, along with other paintings by the painting god Lucien Freud, are two portraits by Freud of the man who is responsible for the existence of this collection:

Lucian Freud

Portrait of Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza

oil on canvas, 1981-82

Look in the background of this painting, over the Baron’s right shoulder, at the strange image there. It is a painting by Watteau titled Pierrot Content, made in 1712. It is one of the paintings in the Baron’s collection, and is also exhibited in the museum.

Pierrot is just sitting in the middle, looking blithe, the center of the symmetrical arrangement of commedia dell’arte characters. Pierrot’s figure in this painting is not even reproduced in Freud’s portrait of the Baron; the Baron’s head obscures it. Yet, only a few years later, Freud again paints the Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza, and whether by coincidence or by the artist’s design, the Baron assumes a position almost equal to that of Pierrot in Watteau’s painting:

Lucian Freud

Man in a Chair (Portrait of Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza)

oil on canvas, 1985

Is Freud saying that the Baron is content like Pierrot, surrounded on all sides by his beauties? So interesting, these connections.

And that’s it, the end of the museum, we have seen everything. Now it’s time to visit the gift shop and spend a few more hours looking at the books.