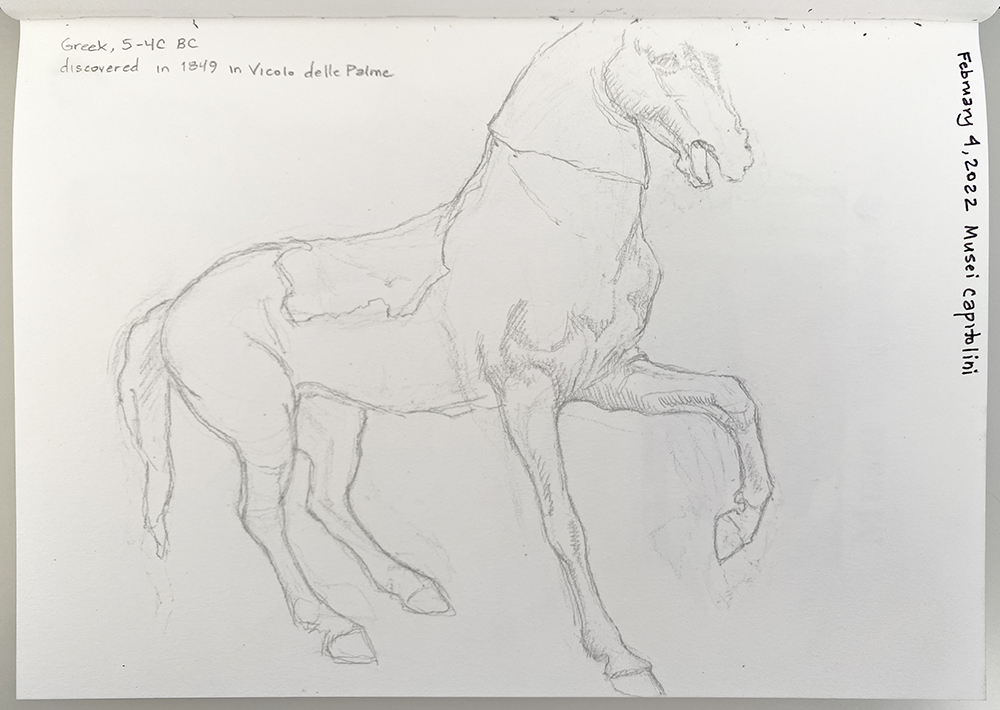

Continuing my collection of the world’s best equestrian bronzes, I visited the horse of Vicolo delle Palme in the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

According to the Museum’s sign, the horse was found in 1849 during excavations on the street now known as Vicolo dell’Atleta in Trastevere. It is an original Greek work from the 4th or mid-5th century B.C., probably brought to Rome as war booty after the conquest of Greece in the mid-2nd century B.C. The gap in its back indicates it once carried a rider.

Archeologists believe that the site where the horse (along with the bronze bull now displayed in the same room) was found may have been a late-Roman or medieval forge, and these two extraordinary works were among a pile of various scrap materials waiting to be smelted.

Being February, only a few weeks after the post-pandemic reopening of museums, the Capitoline was utterly deserted. I attracted the attention of the guards merely by being the only one in the rooms, but also because I was moving very slowly, taking lots of photos of objects, and looking at things from many angles as I contemplated what to draw. I suppose I made them particularly nervous by moving around into the tight (but accessible) spaces behind the horse, trying to see it from all sides. When I finally selected my vantage point and began to draw, the guard in the room next door poked his head in, looked at me strangely, then disappeared. Ten minutes later he returned with a short, officious woman who peremptorily asked me if I had requested permission to draw inside the museum. Feigning utter astonishment (when in reality I wasn’t surprised at all, having lived in Italy long enough now to know to expect this sort of development) I asked innocently, “one needs permission to sketch in an art museum?” The woman explained that yes, it was necessary to write to the Superintendent of something-something, and obtain permission prior to one’s visit. Continuing to draw, I said, “But I am a painting professor, I bring my students here all the time and we always draw, we have never been told this before.” The woman looked a little disconcerted, began calling me Professoressa, and said that the rules had recently changed and that from now on I would need to request permission on behalf of all my students prior to every visit. Still drawing, I said, “Well this is very unfortunate, now I will have to find another place to take my students where artists are more welcome.” The woman and the guard (who now looked sorry that he had called his supervisor in the first place) hastened to tell me that they would get me the e-mail address of the Superintendent, and that surely permission would be granted. They went away and I continued to draw. They came back and solicitously gave me a scrap of paper with an e-mail address written on it in that curly Italian handwriting that we Americans often have trouble deciphering. Pulling out all the stops on my best learned Italian-ness, I made a long production of asking them for clarification on the spelling of the Superintendent’s name, and for help understanding the e-mail address, portions of which I carefully re-wrote in my own handwriting on the same piece of paper. When we were done I struck the coup-de-grace, asking them if I might continue to work on my drawing today, given that there were no other patrons in the museum, I was standing well out of the way, and I had now been informed of the policy. Looking displeased at my lack of respect for their authority, but unsure of what to do about it, they reluctantly left me.